- 玉米蛇宠物饲养询证指南

- 说明

- 本指南建设原则

- 入手前需要什么

- 基本物种信息

- 解剖与生理

- 动物福利总论

- 蛇的行为学

- 爬行动物的认知能力

- 丰容

- 玉米蛇的自然生境

- 玉米蛇饲养的要素

- 空间需求

- 栖地布置总则

- 光照与加热

- 光照的测试

- 湿度

- 垫材

- 攀爬、遮挡与躲避

- 水

- 食物

- 共栖关系

- 蜕皮

- 特殊状态:冬眠和繁殖

- 互动与行为训练

- 运输

- 摄像头

- 伏地魔栖地

- 应急预案

- 蛇的医疗

- 信息来源

- 其他问题

- 词汇表

- 其他物种

【】【那个冯柚子有一个问题宝宝系列】【】

https://reptifiles.com/corn-snake-care-guide/sick-corn-snake-diseases-health/

玉米蛇的常见疾病:【】【Marie Kubiak - Handbook of Exotic Pet Medicine (2020, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated) - libgen.li】【】

16.4 Common Medical and Surgical Conditions

16.4.2 Dysecdysis

The outer keratinised portion of skin is shed in a single piece every three to four months in adults, and this process is termed ecdysis. Growing juveniles shed more frequently at every three to eight weeks (Penning 2012). Low temperatures, ill health, and malnutrition may extend the shedding cycle, whereas ectoparasitism, dermatitis, or endocrine disease may increase shedding frequency (Harkewicz 2002). Disruption to the shedding process, including incomplete or protracted ecdysis, is termed dysecdysis. Inappropriate humidity, dehydration, dermal injury, inflammation or scarring, and debilitation are common factors in dysecdysis. Retained areas of skin may cause irritation or act as a nidus for infection. If the distal tail is affected then progressive contraction of unshed skin can cause avascular necrosis of the tail tip (Harkewicz 2002). Soaking the snake in tepid water for 20–30 minutes can aid in atraumatic removal of retained skin using a damp towel or forceps. Shed skin should not be forcefully removed as this may damage the underlying skin.

In snakes, the eyelids are replaced by a clear skin layer, termed the spectacle (van Doorn and Sivak 2013). The spectacles may be retained in dysecdysis, giving a dull appearance to the eye. This can be seen with generalised dysecdysis, or with localised irritation, such as periocular snake mite infestation. Applying hypromellose drops repeatedly over a 30 minute period may aid in separating the old and new spectacle at the periphery, allowing gentle removal with a cotton bud or forceps. Forceful removal can damage the new spectacle, with exposure of the cornea and potential for permanent eye damage. If the spectacle is not readily removed then correcting causative factors and leaving it to be cast at the next shed is recommended.

Hyperthyroidism is described as a cause of increased frequency of ecdysis in corn snakes, due to primary hyperthyroidism, or hyperthyroidism secondary to pituitary pathology (Whiteside and Gamer 2001; Harkewicz 2002). However, convincing evidence of clinical hyperthyroidism is lacking and reports suggests that hyperthyroidism should reduce rather than increase the frequency of ecdysis (Chiu and Lynn 1970; Chiu et al. 1983; Hunt 2015). Serum thyroxine levels can be assessed in cases of atypical ecdysis frequency, the normal range for free T4 in this species is reported to be 0.45–6.06 nmol/l (Greenacre et al. 2001).

16.4.3 Dermatitis

Dermatitis may present as increased shedding frequency, localised skin retention, alteration of pigmentation, swelling, abscessation, exudative ulceration, or sloughing of tissue (Hoppmann and Barron 2007). Thermal, chemical, bacterial, and fungal causes are well recognised.

Thermal burns are a major differential for dermal injury in pet snakes (Hoppmann and Barron 2007). It has been hypothesised that snakes process thermal stimuli differently to other animals, with a reduced response to noxious thermal stimuli seen (Sladky et al. 2008). This may explain the failure of snakes to move away from malfunctioning or inappropriate heat sources, resulting in contact burns that can be extensive. No external damage may be seen immediately after thermal insult and most snakes only present days later once sloughing of damaged tissues commences. Open wounds may result over a large area of the body surface with potential for significant loss of fluid and protein in exudates, and opportunistic infection. All cases require analgesia and replacing substrate with paper towel or a bare vivarium floor temporarily will aid in keeping traumatised areas clean.

First degree burns are superficial, affecting only the epidermis with erythema and blistering often resulting (Mader 2002). Topical treatment such as silver sulphasalazine or zinc oxide will aid healing, with resolution of lesions in a four- to six-week period.

Second degree burns are associated with necrosis of the epidermis and damage to the deeper dermis. Swelling, blistering, discoloration of skin, and exudative lesions are seen. Systemic antibiotic therapy and topical treatments are necessary for these cases (Harkewicz 2002) but scarring can result. Adhesive sterile dressings can be placed over injuries to prolong action of topical agents and protect the wound (Mader 2002). Maintaining snakes at the top end of their temperature gradient will accelerate healing (Smith et al. 1988). Fluid therapy requirements will depend on the area of the burn and the fluid losses sustained.

Third degree burns have full thickness skin damage with sloughing of skin across the lesion. Fluid therapy is necessary as losses can be significant. Daily bandage changes, systemic and topical antibiotics, and multimodal analgesia are necessary for management of these cases in the first days to weeks of treatment, with ongoing medical therapy and less frequent bandage changes required for the four to six month healing period (Mader 2002). Significant scarring will result and may interfere with ecdysis.

Bacterial or fungal infections are rarely primary concerns, but follow insult to skin integrity such as a burn or bite from prey, or chronic husbandry deficiency such as excessive or insufficient humidity, low environmental temperatures, obesity, unsanitary conditions, or malnutrition (Harkewicz 2002; Hoppmann and Barron 2007). Where substrate is consistently wet or heavily contaminated, the ventrum is most commonly affected and may appear erythematous and develop vesicles or ulceration (Hoppmann and Barron 2007). The underlying cause should be corrected. Skin lesions should be cultured to guide therapy, and antimicrobials, analgesia, topical disinfectants, and debridement and subsequent protection of affected areas using bandaging considered based on severity of lesions. Fungal lesions may require biopsy for confirmation of diagnosis (Hoppmann and Barron 2007).

Primary fungal pathogens are uncommon in captive animals, but Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola (formerly Chrysosporium ophiodiicola) is an emerging disease in wild and captive snake populations and has been reported in colubrid snakes (Allender et al. 2015). Infection in most snakes affects the head and ventral scales with caseation and crusts but the one clinical case reported in a corn snake presented with a subcutaneous nodule (Sigler et al. 2013). O. ophiodiicola has also been demonstrated to cause disease in experimentally infected corn snakes (Lorch et al. 2015). Infected animals in this study developed oedema, crusting, and hyperpigmentation of scales, increased ecdysis frequency and dysecdysis but appeared able to clear the fungal infection following ecdysis (Lorch et al. 2015). For clinical cases, biopsy for fungal culture and histology is recommended, with treatment comprising systemic and topical antifungals. O. ophiodiicola appears poorly responsive to itraconazole and ketoconazole therapy, and voriconazole has been associated with death of snakes at 5 mg/kg (Rajeev et al. 2009; Sigler et al. 2013; Lindemann et al. 2017). Terbinafine has been demonstrated to be effective in vitro, and reaches expected therapeutic levels in c ottonmouths (Agkistrodon piscivorous) with nebulisation or placement of a subcutaneous implant (Kane et al. 2017). Based on the study findings, 30 minutes n ebulisation daily using a 2 mg/ml terbinafine solution was r ecommended as a potential treatment. Oral and topical terbinafine formulations are commercially available but no dosing schedules have been determined. Exposure of spores for 2 minutes to 3% bleach, or for 10 minutes to 70% ethanol or quaternary ammonium products have been shown to be effective for disinfection, but c hlorhexidine and propiconazole were ineffective (Rzadkowska et al. 2016).

16.4.4 Respiratory Disease

In snakes, the right lung is a simple sac, lined with respiratory epithelium cranially and avascular non-respiratory epithelium caudally, resulting in a relatively small surface area for gas exchange (Schumacher 2003). The left lung is vestigial in colubrids. Clinical respiratory disease is common in pet snakes but in the author’s experience, respiratory disease is less common in colubrid snakes than larger, sedentary boids. Clinical signs include nasal discharge, audible respiratory noise, presence of secretions in the oral cavity, stomatitis, dyspnoea, open mouth breathing, elevation of the head and neck, and cyanosis (Schumacher 2003). Disease is often advanced by the time of overt symptoms and presentation. Radiography is of limited value for mild–moderate disease but may show abscess formation, fluid accumulation, or increased radiodensity of the lung in advanced cases. Computed tomography is of higher sensitivity for lesions and is preferred for diagnosing and monitoring respiratory disease but is not as readily available. Ultrasonography may identify increases in fluid or soft tissue and facilitate collection of aspirate samples for culture or cytology (Schumacher 2003). Endoscopy of the trachea is limited by patient size, but swabs can often be collected for culture and PCR diagnostics for upper respiratory tract diseases. Tracheal and lung wash samples are advisable to determine specific pathogen presence in lower respiratory tract disease (Murray 2005). Percutaneous surgical endoscopic access to the lung can be utilised for sample collection or topical therapy of focal lesions.

Bacteria, particularly gram-negative organisms, are commonly isolated from respiratory cases and may be primary pathogens, opportunistic invaders, or co-infections.

Viral respiratory pathogens reported in corn snakes include ophidian paramyxovirus, reovirus, and adenovirus (Abbas et al. 2011). These viruses may be present in clinical cases, asymptomatic animals, or as part of mixed infections (Abbas et al. 2011), so a positive result should be interpreted in accordance with the animal’s clinical status. For paramyxovirus, demonstration of a rising titre is recommended to confirm active infection (Jacobson and Origgi 2002). It is unknown if snakes with static antibody levels have cleared infection or remain permanently infected, though a small proportion of corn snakes experimentally infected with paramyxovirus appeared able to clear infection (Pees et al. 2016). Supportive care may allow recovery in less severe cases. These viruses are highly infectious and can spread within and between collections readily, emphasising the importance of biosecurity, quarantine, and targeted screening of new animals.

Non-infectious respiratory disease is uncommon but may include penetrating injuries, neoplasia, or exposure to irritant gases or aerosols.

Treatment of respiratory disease involves targeted therapy for the primary cause where possible, husbandry improvements, and supportive measures. The lack of a diaphragm, reliance on skeletal muscles for air movement, and lack of a developed mucocilary system means that respiratory secretion clearance is poor in snakes. Fluid therapy, nebulisation, encouraging activity, coupage and drainage of secretions by elevating the mid body above the head may aid clearance of debris in lower respiratory tract disease. Maintaining animals at the top end of their thermal range will aid immune function and maintaining a high humidity level may decrease secretion viscosity, enhancing clearance.

16.4.5 Cardiac Disease

A detailed description of cardiac anatomy and physiology in snakes is beyond the scope of this chapter but major differences will be mentioned. Cranially there are two atria, and caudally a single ventricle, subdivided by a muscular ridge – the vertical septum. The thin-walled sinus venosus, is located dorsal to the right atrium and receives blood from the systemic circulation, contracting prior to atrial contraction to aid filling of the right atrium (Farrell et al. 1998; Jensen et al. 2014). During respiration, the ventricle is functionally divided by the vertical septum to function as a bi-chambered heart, in an equivalent way to mammals. When apnoeic, parasympathetic tone increases resulting in bradycardia and increased pulmonary resistance. Under these conditions blood from the right side of the heart is shunted across the ventricle and a significant proportion of the blood re-enters the systemic circulation, bypassing the pulmonary circulation (Bogan 2017). This reduces cardiac activity when oxygen is unavailable, but maintains perfusion to the systemic circulation.

Cardiac disease may present with regurgitation, anorexia, lethargy, weight loss, peripheral oedema, cyanosis, open mouth breathing, or a discrete swelling (Figure 16.8) (Kik and Mitchell 2005; Beaufrère et al. 2016). Assessment should take place with the snake at an appropriate temperature as cardiac function can alter with hyper- or hypothermia. The cardiac position can be localised on examination by placing the snake in dorsal recumbency and visualising a pulsatile region approximately 20–23% along the length of the body of the snake (Divers 2008). Auscultation with a stethoscope is unrewarding, but Doppler ultrasonic probes can be useful in assessing for alterations in heart sounds (Kik and Mitchell 2005; Mitchell 2009). In another colubrid, the yellow rat snake (Elaphe obsoleta quadrivitatta), creatine kinase rises with myocardial damage and may be useful in supporting a diagnosis of cardiomyopathy (Ramsay and Dotson 1995). For electrocardiography (ECG), lead II is most frequently used. The negative lead is placed one to two heart lengths cranial to the heart on the right, the positive lead placed on the left, approximately 60–75% along the body and the neutral lead placed on the right, opposite the positive lead (Kik and Mitchell 2005; Bogan 2017). The trace has P and T waves and a QRS complex, similar to that seen in mammals but amplitude may be lower, hindering interpretation (Kik and Mitchell 2005). An additional ‘SV’ wave may been seen prior to the P wave, reflecting depolarisation of the sinus venosus (Martinez-Silvestre et al. 2003). ECG interpretation is not yet well described in snakes and caution should be exercised when making a diagnosis based on an ECG alone.

Figure 16.8 Pronounced pulsatile swelling in the cranial coelom indicative of cardiomegaly. Cardiac disease appears common in colubrid snakes.

Radiography, particularly the laterolateral view of the cranial-mid body, may support cardiac disease, with c ardiomegaly, hepatomegaly, pulmonary oedema, vascular mineralisation, or ascites potential findings (Mitchell 2009). Echocardiography may be hampered by poor acoustic coupling but soaking the snake in warm water prior to scanning and using large volumes of coupling gel will aid image quality. A ventral approach is advised, directly over the heart (Schilliger et al. 2006). Potential pathology that can be detected includes pericardial effusion, alterations in valve function or anatomy, parasite presence, neoplasia, or mineralisation of tissues (Bogan 2017). Chamber dilation or thickening of the myocardium may be suspected on echocardiography, but objective assessment is not possible due to a lack of normal values for this species. Cardiomegaly has been reported in this species but prevalence is undetermined (Kik and Mitchell 2005). The author has seen a disproportionately high prevalence of dilated cardiomyopathy in corn and rat snakes, but no evident primary cause has been identified. Treatment for cardiac disease is extrapolated from therapy in domestic mammals though dosing regimens are not validated.

16.4.6 Stomatitis

Oral examination is readily achieved in a restrained snake by gently passing a flat card or blunt probe into the mouth from the diastema at the rostral tip to open the mouth. There are six rows of teeth, two mandibular and four maxillary, with teeth continuously shed and replaced (Mehler and Bennett 2003). The tongue sheath and trachea are identifiable as projections from the floor of the oral cavity.

Petechiation, cyanosis, tacky oral secretions, mucosal inflammation, loss of multiple teeth, haemorrhage, or anatomical asymmetry indicate further evaluation is necessary (Mehler and Bennett 2003). Rostral trauma associated with rubbing on, or colliding with, enclosure walls is uncommon in this species.

Stomatitis or ‘mouth rot’ is a common reason for presentation of captive snakes, and encompasses gingivitis, glossitis, palatitis, and cheilitis from bacterial, fungal, and viral causes. Symptoms may include hyperptyalism, anorexia, dysphagia, loss of teeth, and an irregular appearance to gingiva. Gram-negative bacteria are most commonly isolated from stomatitis cases but there is a significant overlap with commensal bacteria, suggesting external factors may influence development of clinical disease (Rosenthal and Mader 1996). In chronic cases there can be local extension of infection to the nasolacrimal duct, subspectacular space, facial bones, or upper respiratory tract, or distant spread as bacterial emboli or septicaemia. Treatment involves targeted antibiotic therapy based on culture results from lesions, irrigation of lesions using topical antiseptics, and analgesia. Radiographs are useful to determine prognosis and to guide surgical debridement of necrotic or abscessated areas in advanced cases (Mehler and Bennett 2003). For poorly responsive cases histopathology, with particular focus on neoplasia or mycobacteria, and viral screening is advisable.

Ophidian paramyxovirus can result in stomatitis but respiratory and neurological symptoms are more pronounced (Hyndman 2012). Fungal or parasitic stomatitis is rare in captive snakes (Mehler and Bennett 2003).

16.4.7 Ophthalmic Disease

Retained spectacles are the most common ophthalmic abnormality identified in snakes, followed by subspectacular abscess, ocular trauma, and cataracts (Hausmann et al. 2013). Feeding of live prey was found to be a significant cause of ophthalmic trauma and is best avoided.

Subspectacular abscess formation is commonly a consequence of bacterial stomatitis extending along the nasolacrimal duct into the subspectacular space. Colubrid snakes appear more likely to suffer from this condition than other snake families (Hausmann et al. 2013). Animals present with apparent opaque distension of the subspectacular space. The subspectacular space measures approximately 0.14 mm in normal corn snakes (Hollingsworth et al. 2007), but can be increased dramatically with accumulation of purulent material. Systemic antibiotics and anti-inflammatory agents are administered and a 30° wedge resection of the ventral spectacle carried out for drainage and ongoing topical therapy (Cullen et al. 2000). Recurrence is common and may require repeat surgical intervention (Hausmann et al. 2013). Culture of material collected at surgery is advised to guide antibiotic therapy. Staphylococcus spp., Salmonella arizonae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa have been cultured from four cases of subspectacular infections, all presumed to be opportunistic pathogens (Hausmann et al. 2013).

Occasionally an obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct leads to sterile distension of the subspectacular space and treatment involves drainage of the fluid and management of the inflammatory process causing the obstruction. Untreated, these cases can progress to subspectacular abscess formation.

Cataracts have been reported in other colubrids (Martin et al. 1994; Daltry 2006), but appear rare in corn snakes. Phacoemulsification has been used successfully in the closely related Texas rat snake (Ledbetter et al. 2017).

16.4.8 Gastrointestinal Disease

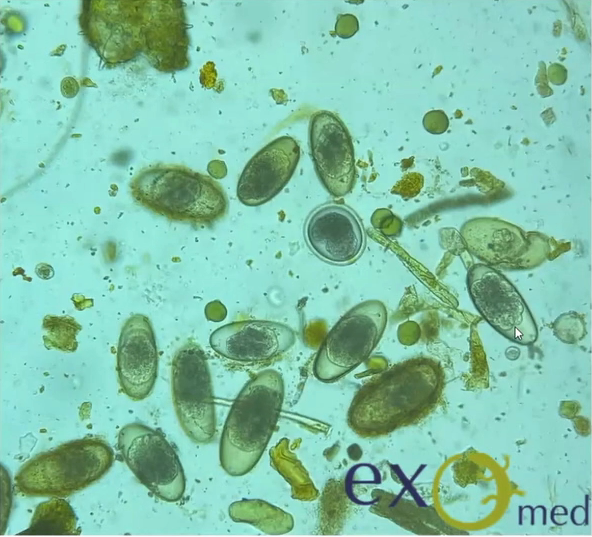

Routine parasite assessment of faecal samples is advisable annually for clinically well snakes, and at presentation for animals presenting for any illness, ideally including testing for Cryptosporidia.

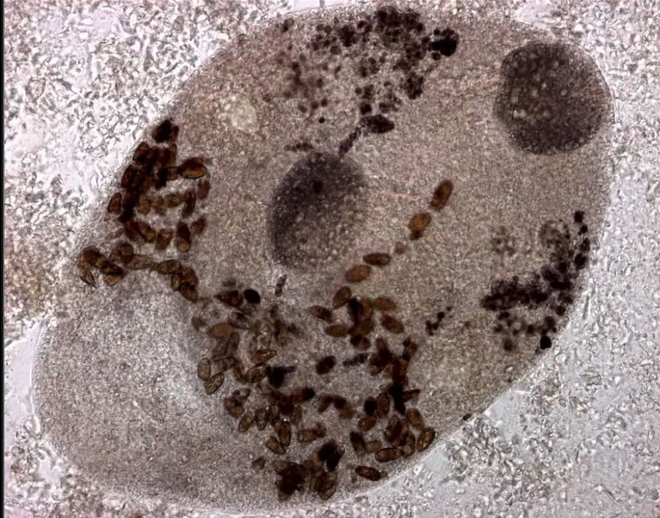

Cryptosporidium coccidia are a significant cause of gastrointestinal disease in reptiles, with Cryptosporidium serpentis recognised as the predominant snake pathogen and Cryptosporidium varanii (syn. Cryptosporidium saurophilum) predominating in lizards, with other species less commonly identified (Xiao et al. 2004; Pavlasek and Ryan 2008; Richter et al. 2011). Oocysts are shed in the faeces of infected animals and remain viable for over a year (Jenkins et al. 1997). Ingestion results in release of sporozoites in the intestinal tract which migrate into the gastric epithelial cells to replicate in snakes (Greiner 2003). Released merozoites can directly infect other epithelial cells and repeat this process, or form gametes to generate oocysts (Greiner 2003). Clinical signs in snakes include regurgitation, gastric distension, weight loss, anorexia, diarrhoea, and incomplete digestion of food (Richter et al. 2011). Chronic gastritis with mucosal hypertrophy, hyperaemia, cobblestone appearance, reduced prominence of rugal folds, and luminal reduction may be noted on endoscopy or post-mortem examination (Cimon et al. 1996; Bercier et al. 2017). Cryptosporidiosis is typically a chronic disease of adult animals, though one case in a oneyear-old corn snake has been reported. In this case, the snake was concurrently infected with adenovirus and it was hypothesised that immunosuppression was a contributing factor to disease development (Mahapatra et al.

2013). Biliary tract cryptosporidiosis and associated cholecystitis has been reported in corn snakes with concurrent intestinal cryptosporidiosis, with no clinical signs of biliary disease (Cimon et al. 1996). A case of oesophageal-gastric-duodenal double compounded intussusception has also been reported as a suspected consequence of cryptosporidiosis in a corn snake (Bercier et al. 2017).

Oocysts are very small and almost transparent so identification on faecal sample flotation can be insensitive. Acidfast staining of samples can increase sensitivity (Greiner 2003). PCR can be performed on faecal samples, gastric wash samples, gastric biopsy, or regurgitated food items and shows greater sensitivity (Yimming et al. 2016). Speciation of cryptosporidia detected by any test is important as Cryptosporidium parvum and Cryptosporidium muris from rodent prey can be present within the intestinal tract following a feed as incidental findings (Greiner 2003). A high detection rate of Cryptosporidia has been reported in corn snakes in one study, with 25% of samples testing positive on PCR (Richter et al. 2011). Interestingly of the 27 positive samples, 17 were C. varanii, one was a similar lizard genotype and the other 9 samples did not achieve a species level diagnosis. In this study it was not determined whether these infections were associated with clinical disease, though other reports suggest that both natural and experimental infection of corn snakes with C. varanii does not appear to result in clinical disease (Xiao et al. 2004; Plutzer and Karanis 2007). Other studies have demonstrated a predominance of C. serpentis, or incidental findings of C. parvum and C. muris, in corn snakes with a positive Cryptosporidium PCR (Xiao et al. 2004; Yimming et al. 2016).

Treatment of infected animals is unlikely to be successful so it is important to quarantine and test new animals prior to introduction into a collection. Weekly testing over a 30 day period has been recommended (Greiner 2003). Halofuginone, spiramycin, and paromomycin have been trialled in snakes but were unsuccessful (Graczyk et al. 1996). Hyperimmune bovine colostrum, has been shown to reduce clinical signs and oocyst shedding in snakes with no side effects, but convincing evidence of clearance of infection is lacking (Graczyk et al. 1998). Complete disinfection of enclosures of infected animals is difficult, as the recommended methods of heat treatment, ammonia-based disinfectants, dessication, and prolonged exposure to ultraviolet light will significantly reduce numbers, but not eliminate viable oocysts (King and Monis 2007).

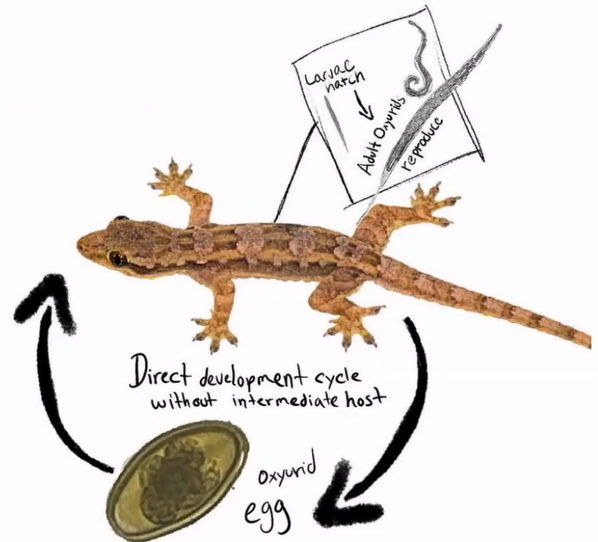

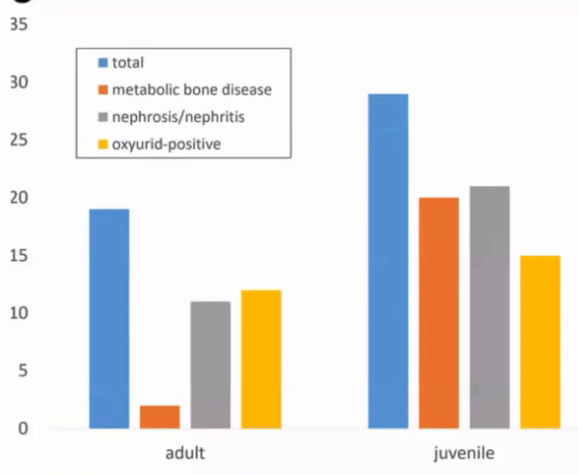

Other endoparasites appear uncommon pathogens in corn snakes. Eimeria oocysts and Ophiostrongylus ova have been identified as co-infections in corn snakes with clinical Cryptosporidiosis (Cimon et al. 1996). Unspecified strongylids were identified in 40% of corn snakes in one study but a wider survey of colubrid snakes found a much lower overall parasitic prevalence with low numbers (<3.3%) testing positive for Kalicephalus, ascarids, heterakids, Rhabdias, Strongyloides, oxyurids, and Balantidium and moderate numbers (7.4%) positive for Nyctotherus (Pasmans et al. 2008; Rataj et al. 2011). Some protozoa may be commensal, but the author has seen clinical signs in colubrid snakes of gas distension of the intestinal tract, foul-smelling liquid faeces, and anorexia in association with high numbers of flagellated motile protozoa on faecal microscopy. Treatment with metronidazole resolves symptoms effectively.

16.4.9 Reproductive Pathology

Dystocia is common in snakes, and inciting factors include a lack of a suitable nesting site, social stressors, dehydration, malnutrition, obesity, pathology of the reproductive tract, renomegaly, and oversized or malformed eggs (DeNardo 2006; Sykes 2010). Presenting signs include failure to complete oviposition of a clutch of eggs, prolonged unproductive straining, oviductal prolapse, or non-specific signs such as lethargy and anorexia in an animal beyond the expected date of oviposition (Sykes 2010). Eggs are relatively large and are often visible and palpable along the ventral surface of the caudal coelom, as a series of soft swellings. Gentle palpation may identify abnormally shaped or sized eggs, but care should be taken as the oviduct is thin and highly fragile (Stahl 2002). Imaging can be used to confirm numbers of eggs present as some, notably the smaller infertile eggs (‘slugs’) may not be as readily palpated. If all eggs appear normal in structure then medical therapy using calcium and oxytocin can be considered. This is not appropriate if oviposition started more than 72 hours previously as response will be poor and there is a higher likelihood of adhesion of eggs to the oviduct wall, risking oviductal rupture (Stahl 2002). Arginine vasotocin is more effective than oxytocin but is not currently commercially available (Millichamp et al. 1983).

An alternative to medical therapy is manual removal, or ‘milking’ of eggs, but this typically requires sedation and carries a significant risk of oviductal trauma so is often not an appropriate approach (DeNardo 2006). Eggs are progressively pushed caudally and out of the cloaca by running a thumb firmly in short strokes along the ventral aspect of the snake. If large eggs are not able to be fully exteriorised, the contents may be aspirated through the vent once the egg is visualised, enabling collapse and easier passage. This is often useful where one oversized egg is preventing oviposition of following eggs. Manual removal should not be carried out after oxytocin therapy as this increases the potential for oviductal rupture (Millichamp et al. 1983).

Percutaneous aspiration is an alternative to enable passage of large eggs. Under sterile conditions a wide gauge needle is inserted, between the first and second row of lateral scales, into the egg (Stahl 2002). The egg contents are aspirated and the snake will then normally pass the collapsed egg within 24 hours (Stahl 2002). There is a risk of ongoing leakage of egg contents into the oviduct and the coelom, resulting in salpingitis or coelomitis, particularly with incomplete deflation. Chronically retained eggs tend to have solid contents and cannot be aspirated (Stahl 2002) and adhesed eggs will not progress.

Surgery is preferred if medical therapy, egg manipulation, or ovocentesis has failed, or where adhesion to the oviduct wall is suspected based on chronicity of signs or immobility of one or more eggs (Lock 2000). General anaesthesia is required, and a lateral coeliotomy is carried out. The skin is

Figure 16.9 Use of everting horizontal mattress sutures for skin closure following salpingotomy.

prepared with a dilute iodine solution, and gently scrubbed between scales using a soft brush. The incision is made directly over the egg, two rows of scales dorsal to the gastric scales with the incision following the scale margins (Bercier et al. 2017). The ribs are transected and the coelomic membrane sharply dissected to visualise the egg within the oviduct. An incision is made in the thin oviduct wall and the egg removed. Additional eggs may be manipulated through the same incision, but often multiple skin and oviduct incisions are necessary to remove all eggs. The oviduct is then closed with a continuous inverting pattern using a 4.0–5.0 long-lasting absorbable suture material such as polydioxanone and the process repeated for the contralateral oviduct, through the same skin incisions. If a prolapse, salpingitis, or oviductal rupture is present, salpingectomy and removal of the ipsilateral ovary is advisable but requires multiple incisions in order to ligate associated vessels and remove all tissues (Lock 2000). An everting pattern such as horizontal mattress sutures, or skin staples, is used for skin closure (Figure 16.9) and sutures or staples are removed at six to eight weeks post-surgery.

16.4.10 Neoplasia

A wide range of case reports of neoplasia have been published for this species, with many affecting young adult snakes of one to five years of age. These are listed in Table 16.3. In the majority of cases a visible swelling is identified (Figure 16.10), though for an oviductal carcinoma, mucopurulent salpingitis without an overt mass was the primary finding (Pereira and Viner 2008).

Table 16.3 Reported neoplasms in corn snakes.

| Neoplasm | Age | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subcutaneous lipomas | Various | Reported to be over-represented in corn snakes | Frye (1994), Reavill and Schmidt (2003), Garner et al. (2004), Dietz et al. (2016) |

| Infiltrative lipoma | Adult; 12 yr | Initial fine needle aspiration (FNA) indicative of lipoma in both cases | Burkert et al. (2002), Pinto et al. (2018) |

| Cardiac haemangioma | 3 yr | Associated with atrial wall | Stumpel et al. (2012) |

| Iridophoroma | 22 yr | No metastasis | Muñoz-Gutiérrez et al. (2016) |

| Malignant mixed chromatophoroma | 17 yr | Metastasised | Muñoz-Gutiérrez et al. (2016) |

| Renal adenoma | Adult | Died 3 m post-surgery | Jacobson et al. (1986) |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 8 yr | Amelanistic, anerythristic morph. Metastasised to contralateral kidney, liver, and lung 3 months after nephrectomy | Barten et al. (1994) |

| Renal adenocarcinoma | 5 yr | Metastasised to contralateral kidney 1.5 months after excision | Kao et al. (2016) |

| Oviductal adenocarcinoma | Adult | No distinct mass, oviduct distended by mucopurulent material | Pereira and Viner (2008) |

| Ovarian undifferentiated carcinoma | 6 yr | 9 × 4 cm mass | Petterino et al. (2006) |

| Pulmonary adenocarcinoma | >1.5 yr | No age given, only time on display | Catão-Dias and Nichols (1999) |

| Adrenal adenocarcinoma | >11 yr | No age given, only time on display | Catão-Dias and Nichols (1999) |

| Cloacal adenocarcinoma | >5 yr | No age given, only time on display | Catão-Dias and Nichols (1999) |

| Intestinal adenocarcinoma | Reported as common in corn snakes, one case with metastasis to liver | Garner (2005) | |

| Colonic adenocarcinoma | 3 yr | Multinodular mass at junction of colon and cloaca | Latimer and Rich (1998) |

| Rhabdomyosarcoma | Retrovirus identified in neoplasm | Lunger et al. (1974) | |

| Leiomycosarcoma | >9 yr | Duodenal | Catão-Dias and Nichols (1999) |

| Fibrosarcoma | 12 yr | Suspected invasion into ribs and spine | McNulty and Hoffman (1995) |

| Metastatic chondrosarcoma | 2 yr | Mandibular primary with metastases in the heart, lung, kidney, pancreas, eye | Schmidt and Reavill (2012) |

| Vertebral chondrosarcoma | Three cases arising from vertebral articulations, metastasis noted in one case | Dawe et al. (1980), Garner et al. (1995), Garner (2005) | |

| Splenic haemangiosarcoma | Adult | Died 1.5 m post-surgery | Tuttle et al. (2006) |

| Myeloid leukaemia | >7.5 yr | Multiple organs affected | Catão-Dias and Nichols (1999) |

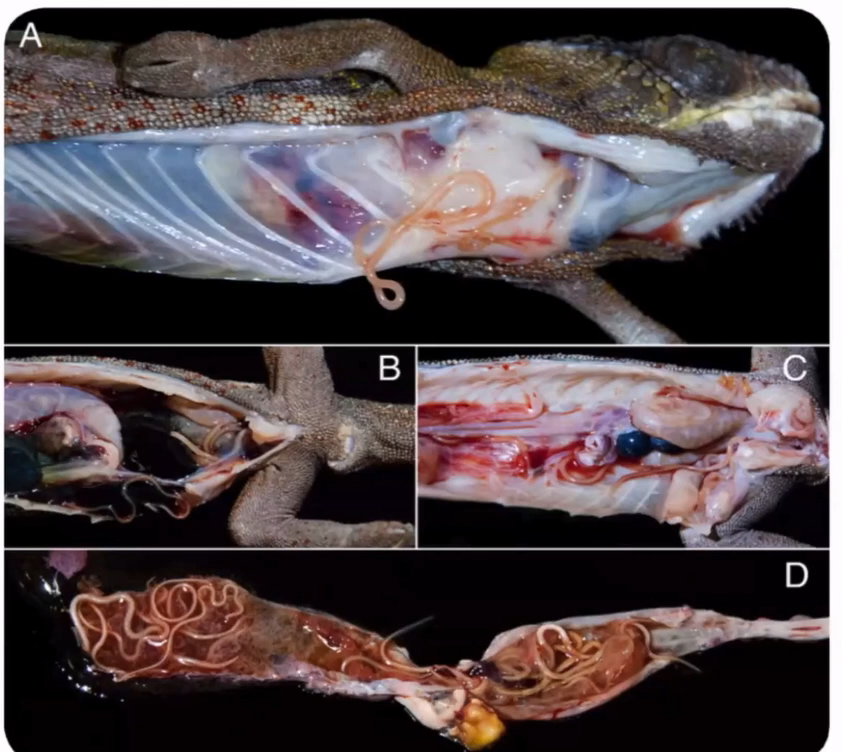

Figure 16.10 Exploratory coeliotomy for investigation of caudal coelomic mass. An intestinal adenocarcinoma was confirmed on histology (Source: Photo courtesy of Sergio Silvetti).

16.4.11 Neurological Disease

Symptoms of neurological disease in snakes include tremors, seizures, incoordination, blindness, opisthotonus, behavioural changes, obtundation and a failure to feed (Fleming et al. 2003; Mariani 2007). Differential diagnoses include toxin exposure (e.g. nicotine, permethrin), thermal injury, severe renal or hepatic disease, physical trauma, malnutrition, adverse response to medication, viral infection (e.g. Ophidian Paramyxovirus, Ophidian reovirus), bacterial infection of the central nervous system, or hypothermia (Mariani 2007). A case series of three corn snakes with clinical signs and histological findings consistent with the viral Inclusion disease of boids has been reported (Fleming et al. 2003). The report concluded that a similar viral cause may be responsible for the disease in corn snakes but no virus was able to be identified.

16.4.12 Renal Disease

In snakes, the right kidney is located cranial to the left and both have a clear overlapping lobular structure. The primary waste product is uric acid, which is expelled as a white paste with small quantities of clear liquid, and can be post-renally modified limiting the value of urinalysis. Renal compromise may result in anorexia, gout, convulsions, and uncoordinated movements (Divers 2008) but appears uncommon in snakes with only one report of nonneoplastic renal pathology in a corn snake. Giant cell nephritis was described by Zwart (2006), with palpable renal enlargement noted on examination, and histology of the swollen kidneys demonstrating interstitial aggregations of multinucleate giant cells.

16.4.13 Ectoparasitism

Mites are a common finding in captive snakes (Harkewicz 2002). The snake mite (Ophionyssus natricis) causes localised irritation, disruption to skin shedding and may act as a vector for pathogens (Harkewicz 2002). Affected snakes may demonstrate an increased frequency of shedding, increased bathing, and adult mites can be observed on the skin, particularly in skin folds around the eyes and mouth (Harkewicz 2002). Ivermectin or fipronil are preferred for treatment. Permethrins can be used but there are reports of toxicity in snakes (Brooks et al. 1998; Whitehead 2010), and the author has seen multiple cases of neurological symptoms in juvenile corn snakes treated with over the counter permethrin sprays that resolved with supportive treatment.

16.6 ocrdonr

16.5 Preventative Health Measures

No routine vaccinations or parasite treatments are recommended. For new animals, a clinical examination, faecal parasite screen, and husbandry review are advisable. Virology screens should be considered based on risk analysis from the originating collection, and size and type of collection the animal is introduced into. For a single pet animal an exhaustive diagnostic panel is rarely appropriate, but if an animal is being introduced into a large, multispecies or high value collection then there is justification to perform a wider array of pre-movement testing and maintain a longer quarantine period of at least six months. Owners should keep good records detailing feeding and shedding schedules and annual faecal parasitology is a sensible precaution.

16.6 Imaging

Radiography is of particular value for skeletal lesions, uric acid depositions, mineralisation of soft tissues, gastrointestinal foreign bodies, dystocia, effusions, and organomegaly (de la Navarre 2006). However, radiography is insensitive in identification of lower respiratory tract pathology (Schumacher 2003) and the coelomic soft tissues offer poor contrast. Contrast studies using barium have been described to enhance detail, but transit time can be in excess of 72 hours (Banzato et al. 2013).

Ultrasonography has been used to assess reproductive status of female corn snakes, with 8–12 MHz linear transducers used to visualise ovarian follicles. The left ovary is found at a distance of 64–75% along the snout-vent length (SVL), and the right ovary is 70–80% SVL (Divers 2008). Pre-ovulatory follicles have a round, uniform hyperechoic appearance in comparison to previtellogenic, hypoechoic follicles (Oliveri et al. 2018). Ocular ultrasonography is also reported in corn snakes, with ultra-high frequency probes necessary (Hollingsworth et al. 2007).

Echocardiography is valuable for subjective assessment of cardiac anatomy and contractility but no reference ranges for measurements have been documented for this species. The liver (30–50% SVL) and intestinal tract (stomach 48–58% SVL [Divers 2008]) can also be assessed readily using ultrasonography.

Nuclear scintigraphy, using 99mTc-MAG3 provides high quality images of the kidneys in corn snakes and may be a valuable tool in the future given the limitations of other methods of imaging (Sykes IV et al. 2006).

Table: Formulary

| Medication | Dose | Interval | Additional comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anaesthesia | |||

| Alfaxalone | 20 mg/kg IM | Inject into cranial half of body, gives 40 mins anaesthesia (James et al. 2018) | |

| Alfaxalone | 5–10 mg/kg IV, IC | Fast onset, 15–20 mins anaesthesia | |

| Propofol | 5–10 mg/kg IV, IC | IV access may not be feasible in all individuals, use lower dose for intracardiac route (Bennett et al. 1998; Stahl | |

| 2002) | |||

| Isoflurane | 2–3% inhaled | Induction may be prolonged. Useful for maintenance at 1–2% (Bertelsen et al. 2005) | |

| Sevoflurane | 4–5% inhaled | Induction may be prolonged. Useful for maintenance at 2–3% (Bertelsen et al. 2005) | |

| Medetomidine and ketamine | 0.15 mg/kg and 10 mg/ kg IM, IV | Useful for sedation, can be partially reversed with atipamezole but recovery may be prolonged (Mosley 2005; Bertelsen 2014) | |

| Metronidazole | 100 mg/kg PO | Two doses, 2 weeks apart | Flagellates (Scullion and Scullion 2009) |

| Fenbendazole | 25 mg/kg PO | Weekly for up to four treatments | Amoebae, flagellates and enteric helminths (Funk and Diethelm 2006) |

| Paromomycin | 300–360 mg/kg PO | q48h for 2 weeks | For Cryptospodiosis, does not eliminate disease in corn snakes (Paré and Barta 1997) |

| Hyperimmune bovine colostrum | 10 ml/kg PO | Weekly for 6 weeks | For Cryptosporidiosis, reduced clinical signs and shedding (Graczyk et al. 1998) |

| Ivermectin | 200 ug/kg SC, IM | repeat after 2 wks | Snake mites (Harkewicz 2002) |

| Analgesia | |||

| Butorphanol | 10 mg/kg SC, IM | q24h | Demonstrated to reduce response to thermal stimulus in one study at 20 mg/kg (Sladky et al. 2008), but respiratory depression possible and this high dose is not advisable (Sladky and Mans 2012) |

| Morphine | 1–5 mg/kg SC, IM | q24h | Effective analgesia in other reptile species. Analgesic efficacy inconsistent in this species (Sladky and Mans |

| 2012) | |||

| Tramadol | 5–10 mg/kg SC, IM, PO | q48h | Extrapolated from other reptile species (Baker et al. 2011) |

| Meloxicam | 0.2–0.3 mg/kg IV, IM, SC, PO | q24–48h | Presumed anti-inflammatory effects (Sladky and Mans 2012) |

| Antibiotics | |||

| Oxytetracycline | 6–10 mg/kg PO, IM, SC | q24h | Injectable preparations can result in localised inflammation (Gibbons et al. 2013) |

| Azithromycin | 10 mg/kg PO | q2–7 days | Based on royal python (Python regius) dose (Coke et al. 2003) |

| Ceftazidime | 20 mg/kg IM, IV | q 48–72h | Used for gram-negative bacterial infections. Third generation cephalosporin, should not be first line antibiotic choice |

| Enrofloxacin | 5–10 mg/kg PO, IM, SC | q24h | Injectable preparations can cause tissue necrosis (Gibbons et al. 2013). Fluoroquinolones should not be first line antibiotics. |

| Terbinafine | 2 mg/ml solution, nebulisation | 30 mins nebulisation daily | To treat fungal dermatosis, including Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola (Kane et al. 2017) |

| Ivermectin | 5 mg/l dilution topically on animals and equipment | repeat after 2 wks | Snake mites (Harkewicz 2002) |

| Fipronil (0.29% spray) | 2 ml/kg topically | q 7–10 days | For ectoparasites, spray or wipe on snake in a wellventilated space, wash off after 5 mins (Fitzgerald and Vera 2006) |

| Miscellaneous | |||

| Furosemide | 2–5 mg/kg IM | q24h | Diuretic for cardiac cases, variable efficacy across species, no data in corn snakes (Selleri and HernandezDivers 2006; Bogan 2017) |

| Pimobendan | 0.2 mg/kg PO | q24h | Extrapolated from lizard dose (Jepson 2009). For dilative cardiomyopathy or congestive heart failure |

| Allopurinol | 20 mg/kg PO | q24h | Decreases uric acid synthesis in renal compromise (Selleri and Hernandez-Divers 2006) |

| Probenecid | 2–4 mg/kg PO | q24h | Increases uric acid excretion, for renal compromise (Selleri and Hernandez-Divers 2006) |

| Methimazole | 2 mg/kg PO | q24h | For hyperthyroidism (Harkewicz 2002) |

| Thyroxine | 0.025 mg/kg PO | q1–5 days | For hypothyroidism (Hunt 2015) |

| Oxytocin | 5–20 iu/kg IM | Start at lower end, repeat with higher dose 6–12 hrs later for maximum of 3 doses | For dystocia (Stahl 2002) |

| Barium 25% | 25 ml/kg PO | For gastrointestinal contrast studies (Banzato et al. 2013) |

Abbas, M.D., Marschang, R.E., Schmidt, V. et al. (2011). A unique novel reptilian paramyxovirus, four atadenovirus types and a reovirus identified in a concurrent infection of a corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus) collection in Germany. Veterinary Microbiology 150 (1–2): 70–79.

Acierno, M.J., Mitchell, M.A., Zachariah, T.T. et al. (2008). Effects of ultraviolet radiation on plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 concentrations in corn snakes (Elaphe guttata). American Journal of Veterinary Research 69 (2): 294–297.

Allender, M.C., Raudabaugh, D.B., Gleason, F.H. et al. (2015). The natural history, ecology, and epidemiology of Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola and its potential impact on free-ranging snake populations. Fungal Ecology 17: 187–196.

Baker, B.B., Sladky, K.K., and Johnson, S.M. (2011). Evaluation of the analgesic effects of oral and subcutaneous tramadol administration in red-eared slider turtles. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 238 (2): 220–227.

Banzato, T., Hellebuyck, T., Van Caelenberg, A. et al. (2013). A review of diagnostic imaging of snakes and lizards. Veterinary Record 173 (2): 43–49.

Barten, S.L., Davis, K., Harris, R.K. et al. (1994). Renal cell carcinoma with metastases in a corn snake (Elaphe guttata). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 25 (1): 123–127.

Bartlett, P.P., Griswold, B., and Bartlett, R.D. (2001). Corn snake. In: Reptiles, Amphibians, and Invertebrates: An Identification and Care Guide (eds. P.P. Bartlett, B. Griswold and R.D. Bartlett), 41–42. Hauppage, NY: Barron’s Educational Series.

Beaufrère, H., Schilliger, L., and Pariaut, R. (2016). Cardiovascular system. In: Current Therapy in Exotic Pet Practice (eds. M.A. Mitchell and T.N. Tully), 151–220. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

Bellamy, T. and Stephen, I. (2007). The Effect of Ultra-Violet B (UVB) Illumination and Vitamin D3 on the Activity, Behaviour and Growth Rate of the Juvenile Jamaican Boa Epicrates subflavus. Master’s dissertation. University of London, United Kingdom.

Bennett, R.A., Schumacher, J., Hedjazi-Haring, K. et al. (1998). Cardiopulmonary and anesthetic effects of propofol administered intraosseously to green iguanas. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 212 (1): 93–98.

Bercier, M., Zoll, W., Rosenberg, J.F. et al. (2017). Gastric intussusceptions in a red corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus) associated with Cryptosporidiosis. Case Reports in Veterinary Medicine 2017: 4270904.

Bertelsen, M.F. (2014). Squamates (snakes and lizards). In: Zoo Animal and Wildlife Immobilization and Anesthesia, 2e (eds. G. West, D. Heard and N. Caulkett), 351–363. Chichester, UK: Wiley.

Bertelsen, M.F., Mosley, C., Crawshaw, G.J. et al. (2005). Inhalation anesthesia in Dumeril’s monitor (Varanus dumerili) with isoflurane, sevoflurane, and nitrous oxide: effects of inspired gases on induction and recovery. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 36 (1): 62–68.

Blackburn, D.G. and Flemming, A.F. (2009). Morphology, development, and evolution of fetal membranes and placentation in squamate reptiles. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution 312 (6): 579–589.

Bogan, J.E. Jr. (2017). Ophidian cardiology – a review. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery 27 (1–2): 62–77.

Bontrager, L.R., Jones, D.M., and Sievert, L.M. (2006). Influence of meal size on postprandial thermophily in cornsnakes (Elaphe guttata). Transactions of the Kansas Academy of Science 109 (3): 184–190.

Brames, H. (2007). Aspects of light and reptilian immunity. Iguana 14 (1): 19–23.

Brooks, J.E., Savarie, P.J., and Johnston, J.J. (1998). The oral and dermal toxicity of selected chemicals to brown tree snakes (Boiga irregularis). Wildlife Research 25 (4): 427–435.

Bull, J.J. (1980). Sex determination in reptiles. The Quarterly Review of Biology 55 (1): 3–21.

Burbrink, F.T. (2002). Phylogeographic analysis of the cornsnake (Elaphe guttata) complex as inferred from maximum likelihood and Bayesian analyses. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 25 (3): 465–476.

Burkert, B.A., Tully, T.N., Nevarez, J. et al. (2002). Infiltrative lipoma in a corn snake, Elaphe guttata guttata. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery 12 (3): 33–35.

Bush, M. and Smeller, J. (1978). Blood collection and injection techniques in snakes. Veterinary Medicine, Small Animal Clinician 73 (2): 211–214.

Calvert, I. (2004). Nutritional problems. In: BSAVA Manual of Reptiles (eds. S.J. Girling and P. Raiti), 289–308. Gloucester, UK: British Small Animal Veterinary Association.

Catão-Dias, J.L. and Nichols, D.K. (1999). Neoplasia in snakes at the National Zoological Park, Washington, DC (1978–1997). Journal of Comparative Pathology 1 (120): 89–95.

Chiu, K.W. and Lynn, W.G. (1970). The role of the thyroid in skin-shedding in the shovel-nosed snake, Chionactis occipitalis. General and Comparative Endocrinology 14: 467–474.

Chiu, K.W., Leung, M.S., and Maderson, P.F.A. (1983). Thyroid and skin-shedding in the rat snake (Ptyas korros). The Journal of Experimental Zoology 225 (3): 407–410.

Cimon, K.Y., Oberst, R.D., Upton, S.J. et al. (1996). Biliary cryptosporidiosis in two corn snakes (Elaphe guttata). Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 8 (3): 398–399.

Coke, R.L., Hunter, R.P., Isaza, R. et al. (2003). Pharmacokinetics and tissue concentrations of azithromycin in ball pythons (Python regius). American Journal of Veterinary Research 64 (2): 225–228.

Cray, C. and Zaias, J. (2004). Laboratory procedures. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice 7 (2): 487–518.

Crocker-Buta, S.P. and Secor, S.M. (2014). Determinants and repeatability of the specific dynamic response of the corn snake, Pantherophis guttatus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology 169: 60–69.

Cullen, C.L., Wheler, C., and Grahn, B.H. (2000). Diagnostic ophthalmology. Bullous spectaculopathy in a king snake. The Canadian Veterinary Journal 41 (4): 327.

Daltry, J.C. (2006). The effect of black rat Rattus rattus control on the population of the Antiguan racer snake Alsophis antiguae on Great Bird Island, Antigua. Conservation Evidence 3: 30–32.

Dawe, C.J., Small, J.D., Banfield, W.G. et al. (1980). Chondrosarcoma of a corn snake (Elaphe guttata) and nephrobastoma of a rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri) in cell culture. In: The Comparative Pathology of Zoo Animals (eds. R. Montali and G. Migaki), 603–612. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institute Press.

DeNardo, D. (2006). Dystocias. In: Reptile Medicine and Surgery, 2e (ed. D. Mader), 787–792. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Inc.

Dietz, J., Heckers, K.O., Aupperle, H. et al. (2016). Cutaneous and subcutaneous soft tissue tumours in snakes: a retrospective study of 33 cases. Journal of Comparative Pathology 155 (1): 76–87.

Divers, S. (2008). Snake radiology: the essentials. Proceedings of the North American Veterinary Conference, 19–23 January, Orlando, FL: 1772–1774.

van Doorn, K. and Sivak, J.G. (2013). Blood flow dynamics in the snake spectacle. Journal of Experimental Biology 216 (22): 4190–4195.

Echternacht, A. and Hammerson, G.A. (2016). Pantherophis guttatus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T63863A71740603. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN. UK.2016-3.RLTS.T63863A71740603.en. (accessed 29 November 2018).

Fahrig, B.M., Mitchell, M.A., Eilts, B.E. et al. (2007). Characterization and cooled storage of semen from corn snakes (Elaphe guttata). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 38 (1): 7–12.

Farrell, A.P., Gamperl, A.K., and Francis, E.T.B. (1998). Comparative aspects of heart morphology. In: Biology of the Reptilia, vol. 19 (Morphology G) (eds. C. Gans and A.S. Gaunt), 375–424. Ithaca, NY: Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles.

Fisher, P.L. and Csurhes, S. (2009). Pest Animal Risk Assessment: American Corn Snake Elaphe guttata. Brisbane: Queensland Primary Industries and Fisheries.

Fitzgerald, K.T. and Vera, R. (2006). Acariasis. In: Reptile Medicine and Surgery, 2e (ed. D.R. Mader), 728. St. Louis, MO: Saunders, Elsevier.

Fleming, G.J., Heard, D.J., Jacobson, E.R. et al. (2003). Cytoplasmic inclusions in corn snakes, Elaphe guttata, resembling inclusion body disease of boid snakes. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery 13 (2): 18–22.

Fonseca, É., Marques, R., and Tinôco, M.S. (2014). New records of Pantherophis guttatus (Squamata: Colubridae) in the state of Bahia, an alien species to Brazil. Salamandra 50: 241–244.

Frye, F.L. (1994). Reptile Clinician’s Handbook: A Compact Clinical and Surgical Reference. Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing Company.

Funk, R.S. (1996). Biology: snakes. In: Reptile Medicine and Surgery (ed. D.R. Mader), 39–46. Philidelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders Co.

Funk, R.S. and Diethelm, G. (2006). Reptile formulary. In: Reptile Medicine and Surgery, 2e (ed. D.R. Mader), 1119–1139. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

Garner, M.M. (2005). Trends in reptilian neoplasia: a diagnostian’s perspective. Proceedings of the North American Veterinary Conference, 8–12 January, Orlando, FL: 1278–1280

Garner, M.M., Collins, D., and Joslin, J. (1995). Vertebral chondrosarcoma in a corn snake. Proceedings of Annual Conference AAZV, August: 332–333.

Garner, M.M., Hernandez-Divers, S.M., and Raymond, J.T. (2004). Reptile neoplasia: a retrospective study of case submissions to a specialty diagnostic service. Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice 7 (3): 653–671.

Gaspar, C. and Dulman, O.M. (2014). Observations regarding the accommodation and feeding of leisure reptiles. Lucrari Stiintifice, seria Medicină Veterinară 57 (3–4): 260.

Gibbons, P.M. (2009). Critical care nutrition and fluid therapy in reptiles. Proceedings of the 15th Annual International Veterinary Emergency & Critical Care Symposium: 91–94.

Gibbons, J.W. and Dorcas, M.E. (2005). Snakes of the Southeast. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press. Gibbons, P., Klaphake, E., and Carpenter, J.W. (2013). Reptiles. In: Exotic Animal Formulary, 4e (eds. J.W. Carpenter and C.J. Marion), 83–182. St. Louis, MO: Saunders.

Graczyk, T.K., Cranfield, M.R., and Hill, S.L. (1996). Therapeutic efficacy of halofuginone and spiramycin treatment against Cryptosporidium serpentis (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) infections in captive snakes. Parasitology Research 82 (2): 143–148.

Graczyk, T.K., Cranfield, M.R., Helmer, P. et al. (1998). Therapeutic efficacy of hyperimmune bovine colostrum treatment against clinical and subclinical Cryptosporidium serpentis infections in captive snakes. Veterinary Parasitology 74 (2–4): 123–132.

Greenacre, C.B., Young, D.W., Behrend, E.N. et al. (2001). Validation of a novel high sensitivity radioimmunoassay procedure for measurement of total thyroxine concentration in psittacine birds and snakes. American Journal of Veterinary Research 62 (11): 1750–1754.

Gregory, P.T., Crampton, L.H., and Skebo, K.M. (1999). Conflicts and interactions among reproduction, thermoregulation and feeding in viviparous reptiles: are gravid snakes anorexic? Journal of Zoology 248 (2): 231–241.

Greiner, E.C. (2003). Coccidiosis in reptiles. Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine 12 (1): 49–56.

Harkewicz, K.A. (2002). Dermatologic problems of reptiles. Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine 11 (3): 151–161. Hausmann, J.C., Hollingsworth, S.R., Hawkins, M.G. et al. (2013). Distribution and outcome of ocular lesions in snakes examined at a veterinary teaching hospital: 67 cases (1985–2010). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 243 (2): 252–260.

Hollingsworth, S.R., Holmberg, B.J., Strunk, A. et al. (2007). Comparison of ophthalmic measurements obtained via high-frequency ultrasound imaging in four species of snakes. American Journal of Veterinary Research 68 (10): 1111–1114.

Hoppmann, E. and Barron, H.W. (2007). Dermatology in reptiles. Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine 16 (4): 210–224.

Hunt, C. (2015). Thyroid adenocarcinoma in a Garter snake (Thamnophis marcianus). Proceedings of BVZS Spring meeting, Loughborough, UK: 38.

Hyndman, T. (2012). Paramyxoviruses in Australian snakes. Doctoral dissertation, Murdoch University, https:// researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/id/eprint/10648 (accessed 15 April 2019).

Jacobson, E.R. and Origgi, F. (2002). Use of serology in reptile medicine. Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine 11 (1): 33–45.

Jacobson, E.R., Long, P.H., Miller, R.E. et al. (1986). Renal neoplasia of snakes. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 189 (9): 1134–1136.

Jakobsen, S.L., Williams, C.J., Wang, T. et al. (2017). The influence of mechanical ventilation on physiological parameters in ball pythons (Python regius). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular and Integrative Physiology 207: 30–35.

James, L.E., Williams, C.J., Bertelsen, M.F. et al. (2018). Anaesthetic induction with alfaxalone in the ball python (Python regius): dose response and effect of injection site. Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia 45 (3): 329–337.

Jenkins, M.B., Anguish, L.J., Bowman, D.D. et al. (1997). Assessment of a dye permeability assay for determination of inactivation rates of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 63 (10): 3844–3850.

Jensen, B., Boukens, B., Wang, T. et al. (2014). Evolution of the sinus venosus from fish to human. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease 1 (1): 14–28. Jepson, L. (2009). Exotic Animal Medicine: A Quick Reference Guide. London, UK: WB Saunders.

Jose, S. (2006). Resident snakes common in other habitats. In: The Longleaf Pine Ecosystem: Ecology, Silviculture, and Restoration (eds. S. Jose, E.J. Jokela and D.L. Miller), 172–173. New York: Springer.

Kane, L.P., Allender, M.C., Archer, G. et al. (2017). Pharmacokinetics of nebulized and subcutaneously implanted terbinafine in cottonmouths (Agkistrodon piscivorus). Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics 40 (5): 575–579.

Kao, C.F., Chen, J.L., Tsao, W.T. et al. (2016). A renal adenocarcinoma in a corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus) resembling human collecting duct carcinoma. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 28 (5): 599–603.

Kik, M.J. and Mitchell, M.A. (2005). Reptile cardiology: a review of anatomy and physiology, diagnostic approaches, and clinical disease. Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine 14 (1): 52–60.

King, B.J. and Monis, P.T. (2007). Critical processes affecting Cryptosporidium oocyst survival in the environment. Parasitology 134 (3): 309–323.

Latimer, K.S. and Rich, G.A. (1998). Colonic adenocarcinoma in a corn snake (Elaphe guttata guttata). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine: Official Publication of the American Association of Zoo Veterinarians 29 (3): 344–346.

Leary, S., Underwood, W., Anthony, R. et al. (2013). AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2013 Edition. Schaumburg, IL: American Veterinary Medical Association.

Ledbetter, E.C., de Matos, R., Riedel, R.M. et al. (2017). Phacoemulsification of bilateral mature cataracts in a Texas rat snake (Elaphe obsoleta lindheimeri). Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 251 (11): 1318–1323.

Lindemann, D.M., Allender, M.C., Rzadkowska, M. et al. (2017). Pharmacokinetics, efficacy, and safety of voriconazole and itraconazole in healthy cottonmouths (Agkistrodon piscivorus) and massasauga rattlesnakes (Sistrurus catenatus) with snake fungal disease. Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 48 (3): 757–766.

Lock, B.A. (2000). Reproductive surgery in reptiles. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice 3 (3): 733–752.

Lorch, J.M., Lankton, J., Werner, K. et al. (2015). Experimental infection of snakes with Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola causes pathological changes that typify snake fungal disease. MBio 6 (6) https://doi.org/10.1128/ mBio.01534-15.

Lunger, P.D., Hardy, W.D. Jr., and Clark, F. (1974). C-type virus particles in a reptilian tumor. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 52 (4): 1231–1235.

Maclean, B. and Raiti, P. (2004). Emergency care. In: BSAVA Manual of Reptiles (eds. S.J. Girling and P. Raiti), 65–66. Gloucester, UK: British Small Animal Veterinary Association.

Mader, D. (2002). Treating burns in reptiles, Proceedings TUFTS Animal Expo, Boston, MA.

Mahapatra, D., Reinhard, M., and Naikare, H.K. (2013). Adenovirus and cryptosporidium co-infection in a corn snake (Elaphae guttata guttata). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 44 (1): 220–224.

Mans, C. and Braun, J. (2014). Update on common nutritional disorders of captive reptiles. Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice 17 (3): 369–395.

Mariani, C.L. (2007). The neurologic examination and neurodiagnostic techniques for reptiles. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice 10 (3): 855–891.

Martin, J.C., Schelling, S.H., and Pokras, M.A. (1994). Gastric adenocarcinoma in a Florida indigo snake (Drymarchon corais couperi). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 25 (1): 133–137.

Martinez-Silvestre, A., Mateo, J.A., and Pether, J. (2003). Electrocardiographic parameters in the Gomeran giant lizard, Gallotia bravoana. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery 13 (3): 22–26.

Mattison, C. (2006). Snake – The Essential Visual Guide to the World of Snakes. New York: DK Publishing.

McNulty, E. and Hoffman, R. (1995). Fibrosarcoma in a corn snake, Elaphe guttata. Bulletin of the Association of Reptilian and Amphibian Veterinarians 5 (3): 7–8.

Mehler, S.J. and Bennett, R.A. (2003). Oral, dental, and beak disorders of reptiles. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice 6 (3): 477–503.

Millichamp, N.J., Lawrence, K., Jacobson, E.R. et al. (1983). Egg retention in snakes. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 183 (11): 1213.

Mitchell, M.A. (2004). Snake care and husbandry. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice 7 (2): 421–446.

Mitchell, M.A. (2009). Reptile cardiology. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice 12 (1): 65–79.

Mosley, C.A. (2005). Anesthesia and analgesia in reptiles. Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine 14 (4): 243–262. Muñoz-Gutiérrez, J.F., Garner, M.M., and Kiupel, M. (2016). Cutaneous chromatophoromas in captive snakes. Veterinary Pathology 53 (6): 1213–1219.

Murray, M.J. (2005). Pneumonia and lower respiratory tract diseases. In: Reptile Medicine and Surgery, 2e (ed. D.R. Mader), 865–877. St. Louis, MO: Saunders.

Nail, A. (2008). Does exposure to UVB light influence the growth rates and behaviour of hatchling Corn Snakes, Pantherophis guttatus? BI6154–Dissertation at Reaseheath College. de la Navarre, B.J. (2006). Common procedures in reptiles and amphibians. Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice 9 (2): 237–267.

Oliveri, M., Bartoskova, A., Spadola, F. et al. (2018). Method of semen collection and artificial insemination in snakes. Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine 27 (2): 75–80.

Paré, J.A. and Barta, J.R. (1997). Treatment of cryptosporidiosis in Gila monsters (Heloderma suspectum) with paromomycin. Proceedings of the Association of Reptilian and Amphibian Veterinarians: 23.

Pasmans, F., Blahak, S., Martel, A. et al. (2008). Introducing reptiles into a captive collection: the role of the veterinarian. The Veterinary Journal 175 (1): 53–68.

Pavlasek, I. and Ryan, U. (2008). Cryptosporidium varanii takes precedence over C. saurophilum. Experimental Parasitology 118 (3): 434–437.

Pees, M., Neul, A., Müller, K. et al. (2016). Virus distribution and detection in corn snakes (Pantherophis guttatus) after experimental infection with three different ferlavirus strains. Veterinary Microbiology 182: 213–222.

Penning, D.A. (2012). Growth rates and prey-handling behavior of hatchling corn snakes Pantherophis guttatus (Colubridae). Doctoral dissertation, University of Central Missouri.

Pereira, M.E. and Viner, T.C. (2008). Oviduct adenocarcinoma in some species of captive snakes. Veterinary Pathology 45 (5): 693–697.

Petterino, C., Bedin, M., Podestà, G. et al. (2006). Undifferentiated tumor in the ovary of a corn snake (Elaphe guttata guttata). Veterinary Clinical Pathology 35 (1): 95–100.

Pinto, F.F., Craveiro, H., Marrinhas, C. et al. (2018). What is your diagnosis? Multiple masses in a corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus). Veterinary Clinical Pathology: 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1111/vcp.12687.

Plutzer, J. and Karanis, P. (2007). Molecular identification of a Cryptosporidium saurophilum from corn snake (Elaphe guttata guttata). Parasitology Research 101 (4): 1141–1145.

Rajeev, S., Sutton, D.A., Wickes, B.L. et al. (2009). Isolation and characterization of a new fungal species, Chrysosporium ophiodiicola, from a mycotic granuloma of a black rat snake (Elaphe obsoleta obsoleta). Journal of Clinical Microbiology 47 (4): 1264–1268.

Ramsay, E.C. and Dotson, T.K. (1995). Tissue and serum enzyme activities in the yellow rat snake (Elaphe obsoleta quadrivitatta). American Journal of Veterinary Research 56 (4): 423–428.

Rataj, A.V., Lindtner-Knific, R., Vlahović, K. et al. (2011). Parasites in pet reptiles. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica 53 (1): 33.

Reavill, D. and Schmidt, R. (2003). Lipomas in corn snakes (Elaphe guttata guttata): a series of four cases. Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Association Reptilian and Amphibian Veterinarians.

Richter, B., Nedorost, N., Maderner, A. et al. (2011). Detection of Cryptosporidium species in feces or gastric contents from snakes and lizards as determined by polymerase chain reaction analysis and partial sequencing of the 18S ribosomal RNA gene. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation 23 (3): 430–435.

Roark, A.W. and Dorcas, M.E. (2000). Regional body temperature variation in corn snakes measured using temperature-sensitive passive integrated transponders. Journal of Herpetology 34 (3): 481–485.

Rosenthal, K.L. and Mader, D.R. (1996). Special topics: microbiology. In: Reptile Medicine and Surgery (ed. D.R. Mader), 119–125. Philadelphia: WB Saunders.

Rzadkowska, M., Allender, M.C., O’Dell, M. et al. (2016). Evaluation of common disinfectants effective against Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola, the causative agent of snake fungal disease. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 52 (3): 759–762.

Schilliger, L., Tessier, D., Pouchelon, J.L. et al. (2006). Proposed standardization of the two-dimensional echocardiographic examination in snakes. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery 16 (3): 76–87.

Schmidt, R.E. and Reavill, D.R. (2012). Metastatic chondrosarcoma in a corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus). Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery 22 (3): 67–69.

Schumacher, J. (2003). Reptile respiratory medicine. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice 6 (1): 213–231.

Scullion, F.T. and Scullion, M.G. (2009). Gastrointestinal protozoal diseases in reptiles. Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine 18 (4): 266–278.

Selleri, P. and Hernandez-Divers, S.J. (2006). Renal diseases of reptiles. Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice 9 (1): 161–174.

Sievert, L.M., Jones, D.M., and Puckett, M.W. (2005). Postprandial thermophily, transit rate, and digestive efficiency of juvenile cornsnakes, Pantherophis guttatus. Journal of Thermal Biology 30 (5): 354–359.

Sigler, L., Hambleton, S., and Paré, J.A. (2013). Molecular characterization of reptile pathogens currently known as members of the Chrysosporium anamorph of Nannizziopsis vriesii complex and relationship with some humanassociated isolates. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 51 (10): 3338–3357.

Sladky, K.K. and Mans, C. (2012). Clinical anesthesia in reptiles. Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine 21 (1): 17–31. Sladky, K.K., Kinney, M.E., and Johnson, S.M. (2008). Analgesic efficacy of butorphanol and morphine in bearded dragons and corn snakes. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 233 (2): 267–273.

Smith, D.A., Barker, I.K., and Allen, O.B. (1988). The effect of ambient temperature and type of wound on healing of cutaneous wounds in the common garter snake (Thamnophis sirtalis). Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research 52 (1): 120.

Stahl, S.J. (2002). Veterinary management of snake reproduction. Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice 5 (3): 615–636.

Stahlschmidt, Z.R., French, S.S., Ahn, A. et al. (2017). A simulated heat wave has diverse effects on immune function and oxidative physiology in the corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus). Physiological and Biochemical Zoology 90 (4): 434–444.

Stumpel, J.B.G., Del-Pozo, J., French, A. et al. (2012). Cardiac hemangioma in a corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 43 (2): 360–366.

Sykes, J.M. (2010). Updates and practical approaches to reproductive disorders in reptiles. Veterinary Clinics: Exotic Animal Practice 13 (3): 349–373.

Sykes, J.M. IV, Schumacher, J., Avenell, J. et al. (2006). Preliminary evaluation of 99mTechnetium diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid, 99mTechnetium dimercaptosuccinic acid, and 99mTechnetium mercaptoacetyltriglycine for renal scintigraphy in corn snakes (Elaphe guttata guttata). Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound 47 (2): 222–227.

Tuttle, A.D., Harms, C.A., Van Wettere, A.J. et al. (2006). Splenic hemangiosarcoma in a corn snake, Elaphe guttata. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery 16 (4): 140–143.

Utiger, U., Helfenberger, N., Schätti, B. et al. (2002). Molecular systematics and phylogeny of Old and New World ratsnakes, Elaphe Auct., and related genera (Reptilia, Squamata, Colubridae). Russian Journal of Herpetology 9 (2): 105–124.

Werler, J.E. and Dixon, J.R. (2004). Corn snake. In: Texas Snakes: Identification, Distribution and Natural History (eds. J.E. Werler, J.R. Dixon and R. Levoy), 107–111. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Whitehead, M. (2010). Permethrin toxicity in exotic pets. The Veterinary Record 166 (10): 306.

Whiteside, D.P. and Gamer, M.M. (2001). Thyroid adenocarcinoma in a crocodile lizard, Shinisaurus crocodilurus. Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery 11 (1): 13–16.

Worthington-Hill, J.O., Yarnell, R.W., and Gentle, L.K. (2014). Eliciting a predatory response in the eastern corn snake (Pantherophis guttatus) using live and inanimate sensory stimuli: implications for managing invasive populations. International Journal of Pest Management 60 (3): 180–186.

Xiao, L., Ryan, U.M., Graczyk, T.K. et al. (2004). Genetic diversity of Cryptosporidium spp. in captive reptiles. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 70 (2): 891–899.

Yimming, B., Pattanatanang, K., Sanyathitiseree, P. et al. (2016). Molecular identification of Cryptosporidium species from pet snakes in Thailand. The Korean Journal of Parasitology 54 (4): 423.

Zwart, P. (2006). Renal pathology in reptiles. The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Exotic Animal Practice 9 (1): 129–159.

- 尽快去医院。如果你无法确定该不该去医院,那就去。除非确实没有条件时再使用替代方法。(此处没有条件指的是像新冠疫情管控之类的不可抗力,不包括:没钱、太远、不熟悉宠物医院在哪儿等等不是理由的理由。)

- 如果你已经知道是什么疾病,可以提前查阅(正儿八经的)兽医教科书和文献进一步判断,有助于与兽医交流并判断出不可靠的兽医。

- 可找靠谱的渠道在线问诊

- 花钱的那种,别去给人发私信像免费使用别人的知识和经验;

- 有的宠物医院的网站或公众号有在线问诊功能;有些兽医会开微博问答;有的医院先电话联系时可以主动询问能否把图/视频发过去做初步判断;

- 在“信息来源”一章列出了个人接触过的部分医生(但我仅能利用读到的更高等级证据时判断哪些医生不好,但没有能力完全判断哪些医生好,只能说“尚未发现不好”)

- 不要“上网查”(即不要用非学术的网页搜索引擎、搜各种无法证实可信度的网站上的信息,各种场合下的“网友回复”只能作为进一步检索的线索,不能直接作为依据)。

DVM: Doctor of Veterinary Medicine

BVS

BVSc

BVMS

BVM

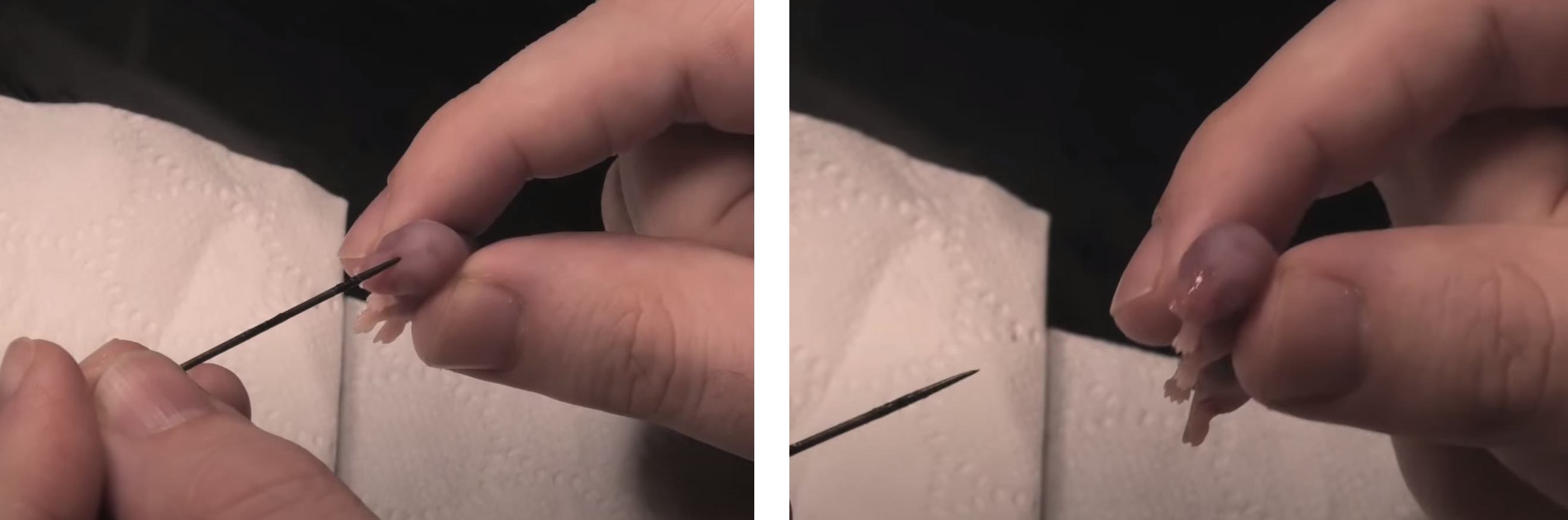

许多头部疾病、口腔疾病(如眼镜卡皮、鼻孔卡皮、口腔炎、呼吸道感染等)需控制蛇头仔细观察,这也是查体的重要环节。许多玉米蛇抗拒被触碰头部,导致没法观察、没法拍照。因此需要学习控制蛇头的正确方法。

一般来说,手的拇指和中指用来支撑头部的侧面,手指位置在枕骨(occiput)后方。食指放在头顶上。用另一只手用来支撑蛇的身体。通过这种方式固定蛇的头部,可以给craniumcervical

junction提供更大的支撑,蛇只有一个occiput,操作不当容易脱臼。

(Mader, 2019 ![]() )IV

)IV

由专业兽医演示的控制蛇的头部进行口腔检查的手法:

应当注意提供对脊椎得支撑,放置蛇头被控制时挣扎导致脊椎损伤。

https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1CJ4m1b7Bz/?spm_id_from=333.999.0.0

- 信息来源:

- S. Divers, S. Stahl, Mader's Reptile and Amphibian Medicine and Surgery 3rd (2019).

- Lori Torrini(多个视频)

- Liam Sinclaie(多个视频)

- 排除所有(专职)繁育者自己的“科普”。网上有大量的类似“教程”是繁育者自己写的,循环论证 + 利益相关。应提高警惕。

- 与繁育者的沟通情况

- 沟通本身的质量是极其重要的评价标准。

- 沟通和互动质量如何?

- 沟通态度是否友好、真诚、耐心?(装作小白,观察其是耐心沟通还是爹味十足。)

- 沟通内容是否谨慎、专业、科学?(把自己说成90分的商家可能有80分,但说自己100分(商品绝无问题/知识绝无错误)的商家、多半不到60分。)

- 回答中提供的信息是否全面?

- 是否了解每条蛇的个性?

- 能否出示相关记录?

- 即使繁育者对下述某些问题回答“不知道”、或是答出了你不想听到的答案,单是其真诚、坦率的正面沟通态度就很重要。

- 动物信息

- 物种/亚种

- 选择物种时应考虑物种的特定性情倾向,例如球蟒的性格使其不宜做第一只蛇类宠物。

- 选择物种时应注意法律状态,对在保物种注意买卖和持有相应动物的合法性;如果有法律要求,应索取/办理相关证件。

- 性别

- 出生日期及年龄

- 幼蛇

- 适应新环境的可塑性强

- 可能有未发现的医疗问题

- 喂食状态不稳定

- 亚成体

- 进食稳定,健康史较长,可以通过询问健康记录排除更多医学问题

- 已受后天经历影响。应了解饲养环境、丰容度、上手互动情况和行为训练情况

- 成体

- 健康史更长

- 个性可塑性较低,改变个性更困难;学习行为和适应新事物会花更长时间。必须详细了解生活史

- 有人出售适繁期的成体应格外注重考察是否患病。

- 幼蛇

- 动物捕获/繁殖状态

- 有些蛇如玉米蛇的繁育非常成熟,一般不出现野苗。但购买其他蛇类,如国内有广泛分布的本土蛇,应注意这些问题。

- WC = wild caught 动物直接从野外捡的

- CH = captive hatch 捡的野蛋,拿回来孵化的

- CB = captive breed 自家蛇下的蛋自家孵化。

- 价格 WC << CH << CB,但应该买CB

- 野补几乎100%携病原体

- WC饲养要求高非常多,常出饲养适应问题、喂食问题,圈养压力响应明显(潜伏状态的疾病会在圈养压力下爆发为有症状疾病),动不动死给你看

- CB常更温顺(证据?)

- 避免对野外种群保护造成压力

- 是否自行繁育?

- 事实核查

- 大部分自行繁育者都喜欢发布交配、产蛋、孵化、喂食等日常照片/视频(而且发布日期应符合物种规律)。如果“全是答案、没有过程”,应当警惕。

- 向销售者提出较为广泛的看货要求,要求看多种蛇、或同种蛇的多种变异,并要求提供视频。此时注意观察不同视频中的环境、饲养方法、出场人物等是否统一。

- 自行繁育者可以应需求拍摄新的素材。可提出一些合理但罕见的要求,比如看脖子的腹侧、看泄殖腔、看尾巴尖之类的,这些视频代理很可能没有提前准备。

- 要求视频电话

- 如果卖家售卖的物种范围过于广泛,常是代理。

- 如果是自行繁育、确认:

- 父母的健康状况、年龄、基因状态?

- 父母/祖父母饲养了多长时间?

- 若不是自行繁育(很多是代理):

- 繁育者是谁?

- 你如何进货的?

- 在你这里养了多久?

- 如果已经养了一段时间,为何考虑要买来这条蛇、现在又要卖掉?

- 国内有时兴“中介”的特色现象,这超出了我的理解能力,不做评述。

- 事实核查

- 有些蛇如玉米蛇的繁育非常成熟,一般不出现野苗。但购买其他蛇类,如国内有广泛分布的本土蛇,应注意这些问题。

- 变异及外观

- 核实变异类型

- 网购时,注意了解各种物种的个体识别特征是什么,例如对某些爬行动物是头纹。做选择和最后收货时应时刻注意个体识别特征,避免视频张冠李戴、避免掉包。

- 如果你在意基因质量,注意蛇是不是近亲繁育集齐罕见基因过程中的”下脚料“

- 注意相关变异成体的外观形态。不要仅看幼体的样貌选购,应关注成体花色是否喜欢。可通过morphmarket.com了解,或要求繁育者出示父母的影像(当然父母的外观不一定和孩子一样)

- 该蛇是否曾参与繁殖、是否曾产蛋(两个问题互相独立)

- 销售者是否有其他宠物(尤其是爬行动物)?如果有,具体是什么情况?末次添加新爬行动物的日期是什么时候?隔离措施如何做的?

- 销售者是否与其他爬行动物接触(包括自己宠物、他人宠物、兽医院接触、出门野采等)?

- 物种/亚种

- 性情测试

- 向出售者询问;

- 该个体的个性如何?

- 是否在幼年提供了足够的运动、丰容和探索机会?这将明显影响身体和智力发育。

- 平时是否有接触新事物的训练?

- 平时是是如何上手的?上手有何响应?(恶劣的“漫灌”式上手训练会影响渐近脱敏)

- 它喜欢进行哪些行为?

- 是否为蛇适应新环境做了准备?

- 是否曾有行为训练?

- 平时的互动状态如何?

- 平时喂食和清洁时蛇有什么反应?

- 试验(自己完成、或由销售者代为完成并做视频记录):

- 打开栖地门/拉出抽屉,后撤远离、观察动物行为

- 打开栖地门/拉出抽屉,接近至接触距离,但不碰触

- 向栖地中置入陌生物体(任何安全且蛇未见过的物体均可)

- 考查做出上述操作时是否出现:

- 行为冻结

- 躲避

- 远离-回避行为

- 警戒姿态、喷气、咬击

- 向门移动

- 吐舌、嗅闻

- 探索/走出栖地

- 爬上手臂

- 向新物体移动

- 爬到新物体附近

- 接触新物体

- 其他行为

- 向出售者询问;

- 病史

- 是否定期体检?请出示记录。

- 有无物种特定的常见病原体检查报告?包括唾液、粪检(病毒、细菌、寄生虫)具体应检查什么看物种决定。

- 个体健康状况如何?

- 当前有无主诉症状?持续时间?

- 以往有无健康问题?

- 有无外伤史?手术史?

- 是否曾就诊兽医,原因是什么?

- 过去30天内,是否曾给予治疗,请给出详细信息

- 动物行为最近是否有变化

- 亲属:

- 兄弟姐妹:

- 有无夭折?

- 有无疾病?

- 繁育者是否追踪了(已卖出的)兄弟姐妹的健康状况?

- 父母:

- 基因?

- 健康状况?

- 生育时父母的年龄(是否在最适生育年龄)?

- 祖父母:

- 是否还健在?

- 兄弟姐妹:

- 其他动物有无遗传病或传染病?

- 周边有无在隔离个体?

- 体检

- 如果只能在线交易,索要一段清晰的视频,观察运动与肌肉状况、皮肤状况、口鼻外观和有无异常分泌物。

- 线下自己做体格检查,并考虑聘请兽医进行专业体检

- 根据物种送恰当的病原体检查,尤其是如果你家还有其他爬行动物时更要注意

- 呼吸、心跳、体温、体长/重量

- 整体状况

- 精神上是否警觉

- 肌肉力量:全身有无用不上力的部位。蛇的“核心力量”应该非常强。蛇尾应可灵活的卷在物体上,前2/3呈悬吊状态时,蛇应该可以用“腹肌”用力把头部拉回手上才对。肌肉力量弱通常体现有严重疾病。

- 神经疾病:如果肌肉力量看着不弱,但是感觉动作不协调,头歪、无法稳定姿态、失去翻正反射等。

- 体型:根据出生日期衡量体型发育是否合理,且不应该太胖/太瘦。

- 头部

- 吻部、口腔损伤(提示严重压力)

- 口部分泌物

- 口腔炎

- 呼吸道疾病

- 眼睛

- 脖颈

- 运动正常

- 无多余物

- 皮肤

- 皮肤状态(应当光泽油亮,排除脱水等问题)

- 有无开放伤口或伤疤(野蛇很多有伤)

- 缺鳞、腐鳞、烫伤、蜕皮不净(尤其注意眼鳞卡皮、尾尖卡皮、鼻孔内卡皮)

- 末次蜕皮日期;既往蜕皮日期记录;蜕皮的状态,是否正处于蜕皮期

- 不要忘了看腹面

- 有无体外寄生虫

- 身体

- 触诊一遍,排除多余肿物和脊椎畸形(kink)

- 泄殖孔和尾

- 干净,无粪便

- 关注梗阻、卡蛋、气味腺肿胀等

- 生活史

- 要想获得优质的互动体验,必须注重繁育者的饲养条件

- 这不只是为了追求动物福利

- 个体的健康水平、精神状态和智力发育与饲养条件的质量直接相关

- 从小有丰容的个体,与从小只有厨房纸、从小天天应激刻板擦玻璃、从小用高强度频繁强迫上手“脱敏”的个体状态完全不同。

- 这部分很多问题不必真的提问,看一眼就知道了;如果销售者有视频频道,可以额外获取很多信息。

- 栖地大小(大的栖地对身体发育有正面作用,避免小栖地长期压力造成的健康问题)

- 是否配备攀爬(树栖)、水域(水生)

- 垫材(纸,玉米芯,沙,树皮,土)

- 丰容物(丰容水平将影响智力发育)

- 通风(钻孔,纱网,风扇;栖地/爬房通风不加会增加患病风险)

- 栖地卫生状况

- 多长时间清理一次?

- 清理时用何种方法消毒、用何种消毒液、如何消毒?

- 如去现场/有视频,应观察卫生状况

- 拍摄视频/应邀参观时已经是经过选择性美化的结果,这种情况下还卫生堪忧的话应直接放弃。

- 喂食

- 出示详细喂食和体重记录,优秀的饲主都应有相关记录。

- 喂食种类:

- 小鼠(冷冻/鲜杀/活鼠)

- 大鼠(冷冻/鲜杀/活鼠)

- 鸟(何种,冷冻/鲜杀/活体)

- 鱼(何种,冷冻/鲜杀/活体)

- 是否使用补剂?如何使用的?(考察各种营养素缺乏/过量问题)

- 多长时间喂一次?是否每次间隔都一样?

- 末次喂食时间;体重和喂食记录;现在是否因消化状态不宜运输?

- 每次喂的数量、重量?是否只能接受特定的大小?(有无喂的大了/带毛了就吐食?)

- 食物是如何呈递的(必须留在栖地内/可以镊子喂食/可以目标引导...)?

- 最近三次喂食的情况,应当均可以自主进食化冻鼠,

- 要求出示一次喂食视频(但注意刚喂食不能运输)

- 食物来源,是否饲喂野生动物

- 进食行为是否正常

- 排便排尿状况如何

- 光照与加热

- 如何加热

- 卤灯、碳纤维加热灯、陶瓷灯、加热垫、(水栖物种)水加热器?

- 加热器如何隔热?动物可触碰表面的最高温度?

- 如何控温的?

- 温度

- 温度是如何测量的?

- 日间晒点,日间冷区?

- 夜间晒点(如果有),夜间冷区?

- 是否提供其他光源

- 可见光:型号和照度

- UVB:型号和上次更换日期(决定是否有缺钙造成的发育异常)

- 光源的昼夜周期设置

- 是否有直射阳光

- 每日多长时间

- 阳光摄入过程中有无玻璃或塑料遮挡

- 如何加热

- 水和湿度

- 何种饮水设施:水碗、滴水器、喷淋

- 换水的间隔;滴水器和喷淋的时间

- 水源:自来水、瓶装水、野外水源

- 是否使用水补剂、水处理剂

- 有无泡澡设施

- 是否监测栖地湿度,湿度多高

- 是否观察有饮水行为变化

- 何种饮水设施:水碗、滴水器、喷淋

- 家中是否有人抽烟或香薰

- 家中是否有人使用雾化装置

- 最近三个月对动物环境做了什么改变

- 要想获得优质的互动体验,必须注重繁育者的饲养条件

- 寄送和售后

- 尽可能当面交易

- 以文字方式固定所有的约定

- 如需寄送:

- 采取何种寄送方式?

- 要多长时间?

- 如何包装?

- 采取何种控温措施?

- 寄送时的全路程天气如何?

- 开箱视频要求

- 提前以文字方式固定要求

- 保证连续、不间断、不出框。(一个注意事项是录制时打开飞行模式,防止中途电话导致视频中断。)

- 注意仔细展示蛇的各个部位,包括微小的问题,如鼻孔、泄殖腔、尾部

- 应保存一段时间

- 三包服务

- 包含何种内容,如保证存活、健康(无伤,无脊椎畸形,无多余肿物)、无进食问题等?

- 期限是多长?

- 有无长期技术支持?如何联系?

- 注意很多繁育者的动物福利水平极差,应自己查询更高质量的证据,其提供的饲养方法和医学建议应谨慎参考。

- 可以先装作不懂、问一些你明确知道答案的问题,考察其知识上线在哪儿。

- 繁育者是否叮嘱在出现医疗问题告知繁育者?(关心血系健康的繁育者会希望了解售出个体的健康状况)

- 购买后可否用于繁育?

- 繁育者是否反问饲主

- 高水平(高动物福利)的繁育者常对饲主的饲养条件有要求,在交货前常会审核饲主是否已完全做好准备。繁育者若会反过来考察饲主的饲养水平是加分项。

一定不要以“救助有病动物”或者“让动物脱离极差环境”的心态用买蛇来救助。垃圾繁育者、垃圾宠物店的东西一定不要买。你从那儿买了只会让这些垃圾继续在同样环境里让更多动物遭殃。III

去逛了宠物店、爬展之后(尤其是摸蛇之后)一定要充分清洁,否则可能往家里传递爬行动物传染病。IV(Mader, 2019 ![]() )IV

)IV

如果你了解同一个卖家的其他动物,可以通过你了解的别的物种的情况考察即将购买的新物种的情况。(比如你养过守宫,想买玉米蛇,而店中两种物种都有,可以先去看看同一家店的守宫的状态怎么样。)II

【】【2019医书有一章未整理】【】

(Mader, 2019 ![]() )IV

)IV

伏地魔消毒

【造景缸如何铲屎】 如何铲屎,溜蛇,手电筒 【生态缸】

煮沸法消毒时必须至少保持沸腾1~3分钟。注意有些材料无法煮沸消毒,煮沸杀灭了生物污染物,但会产生化学污染物。

。立即清除废物和被污染的基质,并至少每3-4个月更换所有基质一次。

III 水盆的清洁,Reptifile 如果在此之前被弄脏,则使用如F10SC、Rescue或氯己定等动物安全的消毒剂清洗后再填充。

Bioactive enclosure

Bioactive enclosure只是方便饲主,并不一定能提高动物福利。https://youtu.be/DM4vbvm5j1Y

【消毒】

【】【Snake Discovery有两个视频】【】

- 用肥皂水刷洗是其他消毒方法的第一步,不首先去除多余的有机质会影响消毒剂效果

- 高温

- 水煮:水煮适合消毒土壤

- 喷湿后微波加热(可能是瓦泥小守宫说的)

- 水煮人工合成聚合物材质的装饰物(如假植)常导致其因接近熔点而变形,

- 蒸汽消毒机

- 烘干机用于消毒织物材质的丰容物

- 75% 乙醇/异丙醇水溶液,比如挥发干净后再放蛇,对蛇有毒(毒性多少?)。

- F10SC,对宠物安全(可能是瓦泥小守宫说的)

- 活得生物质不做消毒,定期弃去(如苔藓)

- Loritorrini推荐的对cork bark管状躲避的消毒:如果来源与爬行动物无关,且没有其他爬行动物用过,可以不做消毒。如果要消毒,首先用肥皂水刷洗;然后用accelrated过氧化氢产品浸泡(比如Accel或Rescue品牌)

F10SC

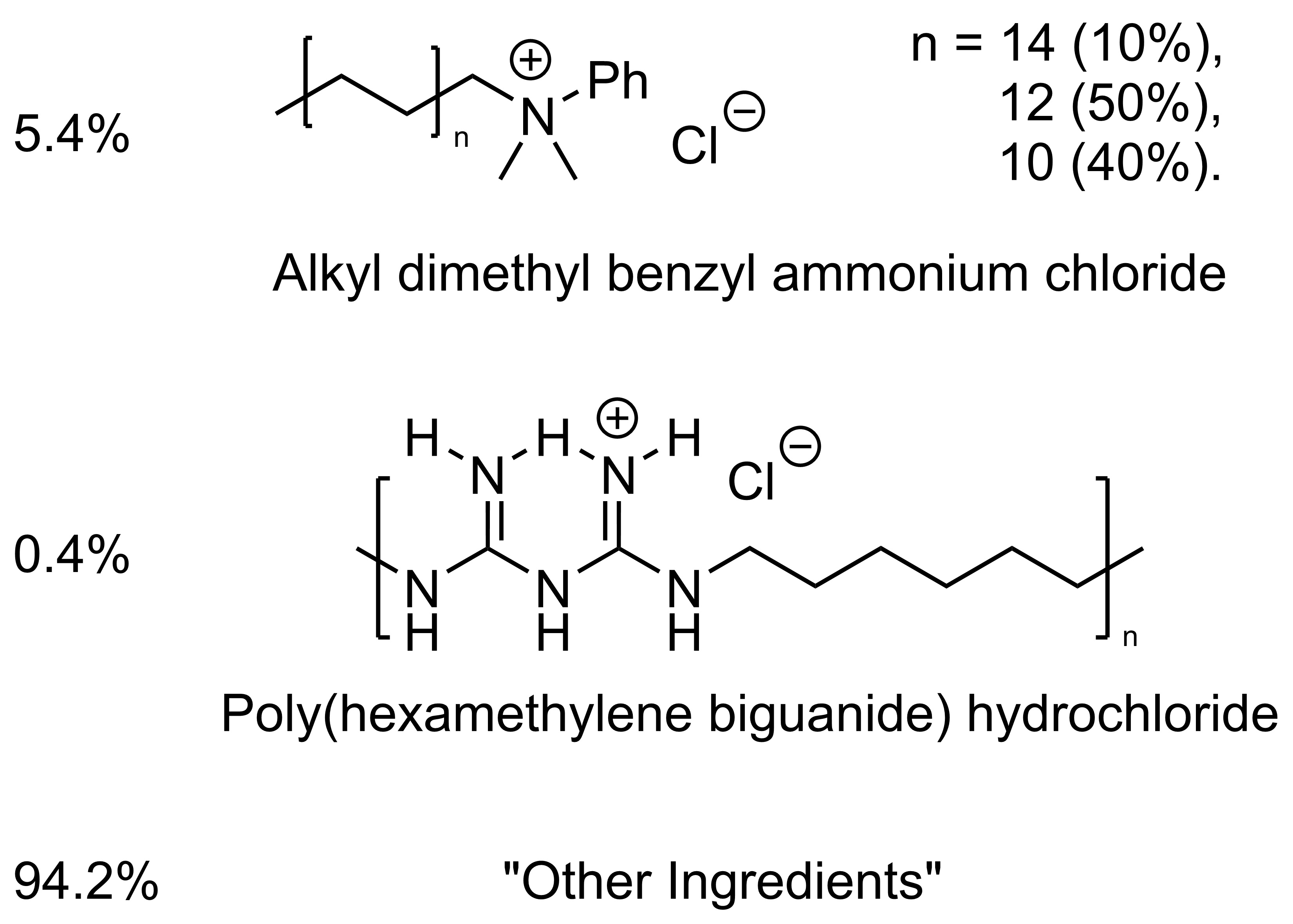

Indications: For the treatment and control of upper and lower respiratory tract disease associated with bacterial, fungal, or viral organisms susceptible to benzalkonium chloride and polyhexanide in raptors, pet birds, captive small mammals, and captive reptiles.

For use as a topical antiseptic for surface wounds on raptors, pet birds, captive small mammals, captive reptiles, and captive exotic/zoo mammals.

Use only when there is a reasonable certainty that the treated animal will not be consumed by humans or food-producing animals.

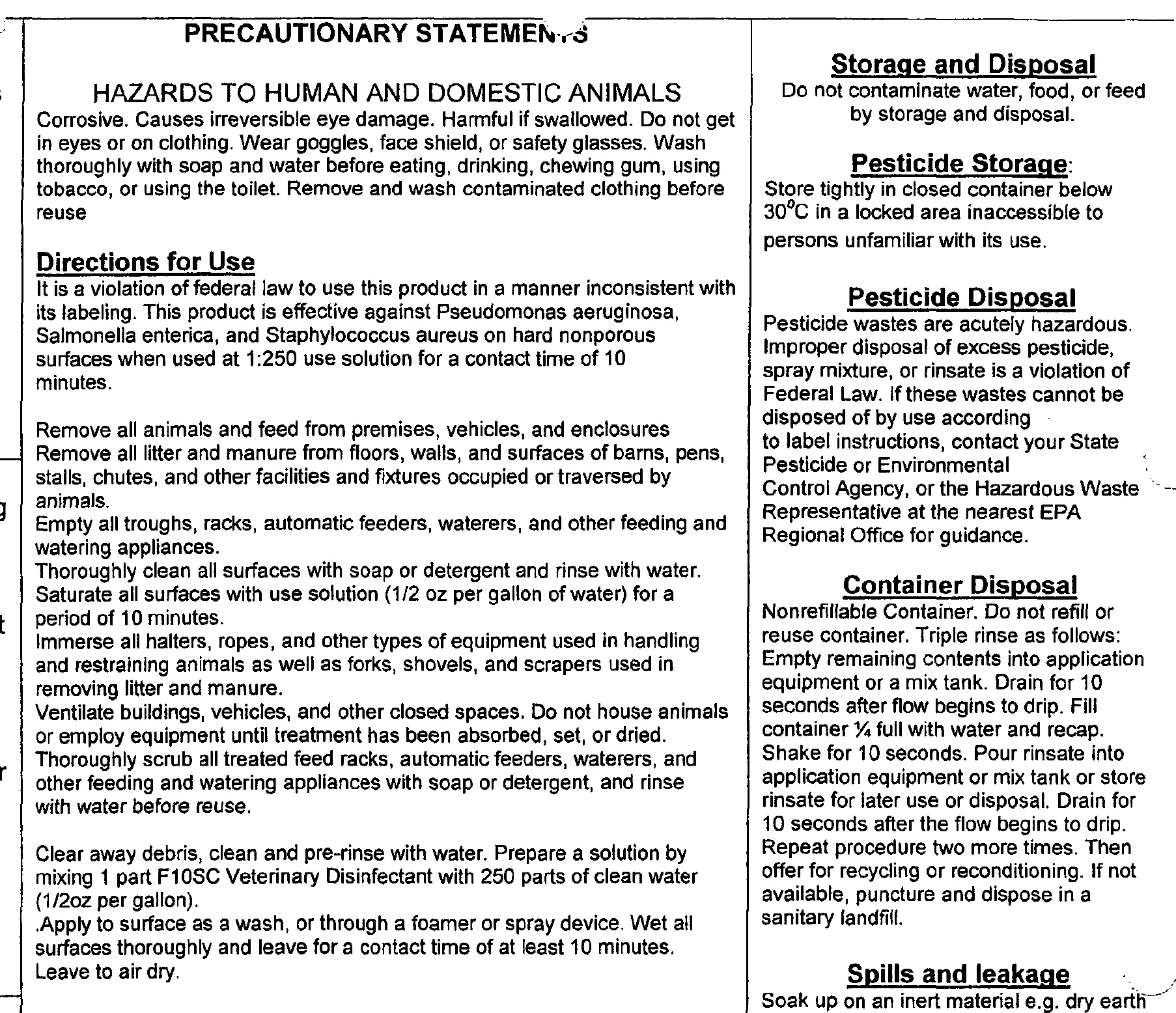

Dosage and Administration: Dilute the concentrate 1:250 with normal saline solution prior to use.

Nebulization: