Explaining the Problem of the Federal Budget and the Debt -

An open letter.

The Federal Deficit and the Debt tend to be highly partisan issues in terms of rhetoric. However, in terms of actions, Washington DC has been sadly consistent - do nothing. Democrats claim that if we would just stop blowing our money on Military Spending, the deficit would magically disappear, and that in the mean time, we can borrow and deficit spend indefinitely with no negative consequences. Republicans say that the debt is a problem, but they are more interested in cutting taxes than in cutting spending. And while they will sometimes make noises about “entitlement programs” needing reform, spending continues unabated, with no serious attempts to rein it in.

Part of the issue is that voters don’t understand the budget and the debt, and therefore politicians know they can’t do anything about it without suffering serious blow-back - so I’m going to try to explain the Federal Budget and the debt problem, and then maybe we can finally start talking about this looming disaster in a serious way - Because politicians will only address the issue once voters say, “This is an issue!” and put our votes where our mouth is.

Part 1: The Federal Budget:

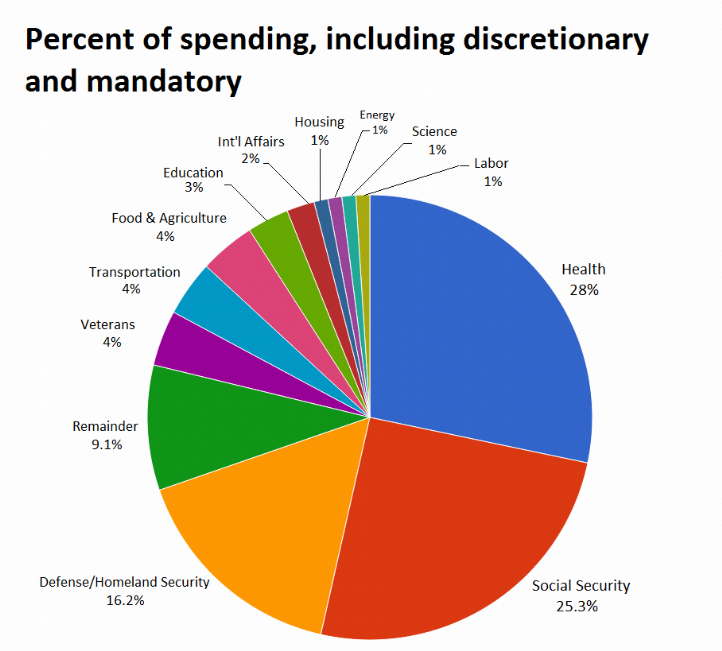

It is crucial to understand this. Many seem to be unaware that military spending is not, in fact, the majority of Federal Spending.

A brief explanation: The blue “Health” and red “Social Security” portions of the budget constitute the category of “Mandatory Spending.” They are ostensibly funded through payroll taxes, which are paid 50/50 by employees and employers. Mandatory Spending accounts for over 60% of federal spending every year, and in recent years has climbed to nearly 70% of federal expenditures.

| Year | Total Spending (trillions) | Mandatory/Entitlement Spending (trillions) | %Mandatory Spending |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2.98 | 1.86 | 62.42% |

| 2009 | 3.52 | 2.30 | 65.37% |

| 2010 | 3.46 | 2.09 | 60.40% |

| 2011 | 3.60 | 2.30 | 63.89% |

| 2012 | 3.54 | 2.26 | 63.70% |

| 2013 | 3.45 | 2.31 | 66.96% |

| 2014 | 3.51 | 2.35 | 66.95% |

| 2015 | 3.69 | 2.30 | 62.36% |

| 2016 | 3.85 | 2.43 | 63.04% |

| 2017 | 3.98 | 2.78 | 69.85% |

| 2018 | 4.11 | 2.81 | 68.37% |

| 2019 | 4.45 | 3.10 | 69.66% |

| 2020 | 4.79* | 3.35 | 69.98% |

The remainder of the budget is “Discretionary Spending,” and this is the part for which Congress proposes a new budget bill every year. Military is the largest spending category in Discretionary spending, typically accounting for about half of the Discretionary Budget. As a percentage of total spending, military spending has fallen over the last 12 years from around 25% to around 15%. It has also fallen in terms of absolute $$ spent.

| Year | Total Spending (trillions) | Military Spending (trillions) | %Military Spending |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2.98 | 0.79 | 26.58% |

| 2009 | 3.52 | 0.82 | 23.35% |

| 2010 | 3.46 | 0.85 | 24.60% |

| 2011 | 3.60 | 0.85 | 23.72% |

| 2012 | 3.54 | 0.80 | 22.71% |

| 2013 | 3.45 | 0.74 | 21.30% |

| 2014 | 3.51 | 0.63 | 17.98% |

| 2015 | 3.69 | 0.62 | 16.69% |

| 2016 | 3.85 | 0.61 | 15.90% |

| 2017 | 3.98 | 0.61 | 15.20% |

| 2018 | 4.11 | 0.63 | 15.40% |

| 2019 | 4.45 | 0.72 | 16.09% |

| 2020 | 4.79* | 0.63 | 13.22% |

*Spending for 2020 is not finalized, and in light of COVID-19, will greatly outweigh the 4.79 trillion that was projected.

Part 2: The Deficit and the Debt.

Now we can ask, “So What? Does it really matter how the government is allocating our tax dollars? I mean, sure, I may not agree all the time, but they’re getting the job done, right?”

Well, perhaps it would be fine to take this line - if the government weren’t exceeding its income. Let’s find out by just how much.

| Year | Total Spending (trillions) | Total Government Revenue (trillions) | Deficit: Spending-Less-Revenue (trilions) | %Of Spending Which is Funded by Debt |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2.98 | 2.52 | 0.46 | 18.25% |

| 2009 | 3.52 | 2.10 | 1.42 | 67.62% |

| 2010 | 3.46 | 2.16 | 1.30 | 60.19% |

| 2011 | 3.60 | 2.30 | 1.30 | 56.52% |

| 2012 | 3.54 | 2.45 | 1.09 | 44.49% |

| 2013 | 3.45 | 2.78 | 0.67 | 24.10% |

| 2014 | 3.51 | 3.02 | 0.49 | 16.23% |

| 2015 | 3.69 | 3.25 | 0.44 | 13.54% |

| 2016 | 3.85 | 3.27 | 0.58 | 17.74% |

| 2017 | 3.98 | 3.32 | 0.66 | 19.88% |

| 2018 | 4.11 | 3.33 | 0.78 | 23.42% |

| 2019 | 4.45 | 3.46 | 0.99 | 28.61% |

| 2020 | 4.79* | 3.71 | 1.08 | 29.11% |

| Average | 3.76 | 2.90 | 0.87 | 32.28% |

As you can see, our government spends 32% more on average than its revenue This means that on average, nearly a full third of our spending is funded by increased debt alone. And this, of course, accumulates. So now let’s take a look at how this debt is accumulating over time.

| Year | Total Government Revenue (trillions) | Cumulative Debt (trillions) |

|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2.52 | 10 |

| 2009 | 2.10 | 11.9 |

| 2010 | 2.16 | 13.5 |

| 2011 | 2.30 | 14.8 |

| 2012 | 2.45 | 16 |

| 2013 | 2.78 | 16.7 |

| 2014 | 3.02 | 17.8 |

| 2015 | 3.25 | 18.1 |

| 2016 | 3.27 | 19.5 |

| 2017 | 3.32 | 20.2 |

| 2018 | 3.33 | 21.6 |

| 2019 | 3.46 | 22 |

| 2020 | 3.71 | 25* |

This is the 2020 debt so far*. It may increase with further coronavirus “relief” spending.

Part 3: The Problem

I find myself hoping that as you read this you have the same kind of visceral reaction that I do. This. Is. Scary. If my personal finances looked like this, there isn’t a bank on Earth that would float me a loan. So far, other countries do seem to be willing to continue to buy our bonds, but eventually the s*** is going to hit the fan, and when that happens, we will have to cut nearly $1 trillion from our spending basically overnight (remember $870 billion from the table above) - and that’s a low-end estimate, because subsets of our bonds are coming due all the time, and currently we borrow to pay them off. When our credit finally sours and we can no longer do this, we will have to direct our tax revenue towards paying off bonds instead of towards government programs.

And when that happens, all those who rely on Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, and other Social Welfare programs will be left in the lurch with no time to make another plan.

Now to clarify the problem. Specifically: is the problem lack of revenue? Or is it too much spending? Well, I would suggest that “the problem” is that there has been no concerted effort to eliminate the deficit by any means. Eg, there has been a failure to acknowledge the problem. Increasing federal revenue (Aka, higher taxes) may be one possible solution to the problem, just as decreasing spending (Aka, cutting “entitlement” and/or military spending) may be another possible solution. But the key is that this problem is real, it needs to be dealt with, and all possible solutions need to be discussed.

If raising taxes is to be part of the solution, that tax increase needs to be specifically for combating the debt, and not for new spending. The government has, in fact, enjoyed increasing revenues since 2008 on the back of an ever-growing economy. But unfortunately, increases in spending have outpaced that growth. I would suggest that spending is the real boogeyman here. And, as military spending has been decreasing while “entitlement” spending has been increasing - and is nearly 70% of all spending - I suspect that “entitlements” are where the real problem lies.

And perhaps this is the true problem, when it comes down to it. Because no one wants to touch “entitlements.”

Part 4: Why won’t politicians fix the problem?

The Devil is in the name: “Entitlement.”

Politicians have been telling people ever since Lyndon Johnson’s “Great Society” and FDR’s “New Deal” that they are entitled to certain payments from the Federal Government - even if those payments are funded with other people’s money (in this case our grandchildren’s and great-grandchildren’s money). Politicians on both sides of the aisle know that if they touch “entitlement” spending, they will not be re-elected. So they don’t touch it - even though cutting our deficit now would save the American people a lot of hardship in the future.

Worse, politicians spread misconceptions about entitlements in order to justify their inaction. I’d like to look at a couple of those misconceptions now.

Misconception number 1: Congress can only influence Discretionary Spending.

The truth is that Congress could completely overhaul Mandatory Spending within a single legislative session, if they so chose. It is true that this would require more dramatic legislation than a typical spending bill - Mandatory Spending is calculated based on prior legislation, and it is that legislation which would need to be changed - but “entitlements” are not off-limits in any legal sense.

Misconception number 2: Social Security and Medicare are fully funded by payroll taxes, so you’re just getting out what you put in, and you are entitled to that money. It’s like a savings program.

The truth is that nearly everyone takes out more from Social Security and Medicare Part A than what they (with their employers) contribute to those programs. Why? For a few reasons. The first reason is that what you get out of Social Security is adjusted - not only for inflation, but also for increases in the “cost of living.” And it’s politically popular to continue increasing this number over time - so they do. The second reason is that, unlike a private retirement account, Social Security isn’t invested, and so doesn’t grow. If you were able to invest the money that you contribute to Social Security via payroll taxes, you would conservatively have about 20X the money on the other end that you can expect to receive in Social Security payments. The third reason is that life expectancy keeps increasing. Social Security was calibrated to a 61 year life expectancy, since that was the life expectancy in 1935 when Social Security started. We’ve made some adjustments on that score (obviously you’re not eligible to collect Social Security now until you’re 65), but not enough to compensate.

Likewise, when it comes to Medicare, increasing lfe expectancy has resulted in increased costs. In addition, the costs of medical products keep increasing - partially due to government actions, and partially due to the development of new medicines and treatments.

Medicare and Social Security essentially are forced-participation Ponzi Schemes, in which they only survive by enrolling an ever larger number of young taxpayers in the system. This is obviously unsustainable, and, as is clearly observable in the data, results in our having to borrow in order to keep the programs going.

Can you imagine borrowing money to invest in your retirement account? These are not savings programs.

Misconception number 3: Medicaid, which is intended as a backstop for the impoverished, needs to be expanded because it doesn’t cover enough people.

The truth is that over 20% of the US population is covered by Medicaid (70 million people). This seems like a huge number. Do our impoverished really constitute a full fifth of our population? In addition, only half the cost of Medicaid is covered by the Federal Government (the rest is paid for by states), so half the cost is hidden if we only look at Federal spending. For that price, it had better be killer insurance! The reviews I’ve heard have been mixed.

Between Medicare and Medicaid, nearly 40% of all Americans are covered by (enrolled in) some kind of Government medical insurance (Medicaid 21%, Medicare 18%)

Part 5: What do we need to do?

We need to balance the budget - which means eliminating the deficit, and then finally beginning to pay down the debt. Simply eliminating the deficit on a permanent basis would have a huge positive impact on our nation’s credit, and therefore paying down the debt itself could be done in slow increments without fear of having the whole system collapse atop our heads.

How do we do this? Well, we need to make up an average of $870 billion per year between cuts to spending and increased tax revenues. I would recommend as a first step that we FREEZE spending - that we do not allow any further increases in total Federal expenditures. We would have to make changes to Mandatory Spending programs in order to make this work (remember that Mandatory Spending is the part of the budget that keeps growing). Then, so long as we don’t stifle the economy, and we rebound from COVID-19, we can expect tax revenues to increase slowly on their own without increasing tax rates. It may be possible to further increase revenue by temporatily increasing tax rates as well, but this is not a simple calculation, as increased taxes depress economic growth. That calculation is outside the scope of this letter.

Given enough time, the simple measure of freezing our spending may be sufficient to overcome the gap between government revenues and government spending - my personal preference, however, would be to take a more aggressive stance and aim to eliminate the deficit within four or five years. This would allow us to begin paying down our debt, which is of course the ultimate goal.

What do Politicians need to hear from us in order to be willing to eliminate the deficit?

Politicians on both sides of the aisle have acknowledged for a long time that Social Security and Medicare are unsustainable in their current form, but have been unwilling to take the plunge and reform them - because the American People haven’t had the stomach for self-imposed government austerity. We’re all for reducing the deficit, but not if it means possible cuts to our favorite programs. No one wants to lose their Social Security benefits. No one wants to cut food stamps, or infrustructure, or medical care…and people like me don’t want to cut the military budget. But we all have to recognize that living within our means is of primary importance - especially for the children and grandchildren to whom we leave this Great Country. We need to decide that our sacrifice in the present is worth having a sound monetary system and a financially independent government in the future. Too many of our foreign policy decisions are wrapped up in sustaining our debt; too many of our government programs are becoming empty promises.

We need to stand up and say, “I demand cuts to spending, even if some of it is the spending that I like. And I am putting my vote where my mouth is.”

Then all we have to do is keep our word.